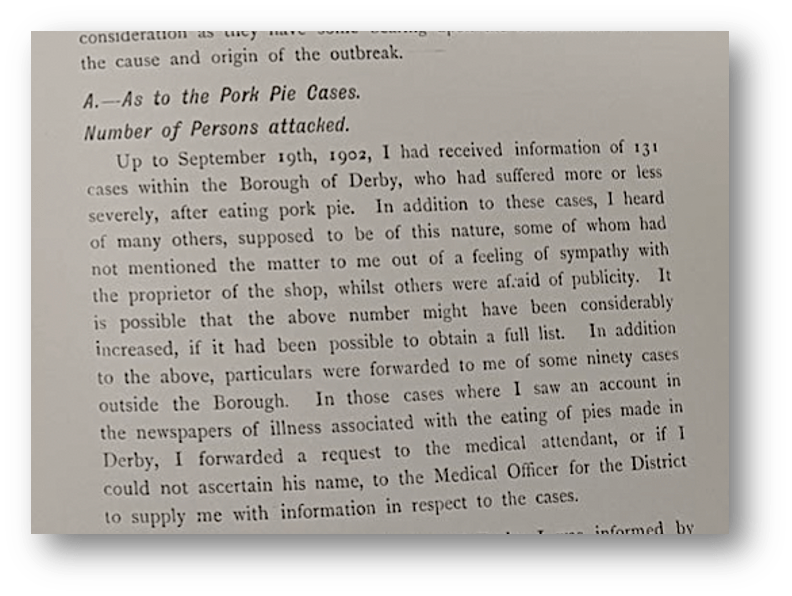

William. J. Howarth, the Medical Officer of Health for the Borough of Derby (MOH), produced the Report on the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning following Derby’s pork-pie incident at Mr Cope’s butchers in September 1902. His report was forwarded to the Sanitary Committee with recommendations to ‘prevent’ future incidents of food poisoning occurring on the premises. By the twentieth century, the belief that food could easily transmit particular bacteriological diseases attracted considerable scientific and public interest.[1] A section of Howarth’s report on the incident can be seen to the left. Howarth’s report draws attention to the interrelationship between those observing, studying, and ‘preventing’ illness in Derby while highlighting associated cases of food poisoning outside the Borough. He also emphasises the importance of ‘respectability’ when it came to reporting the incident.

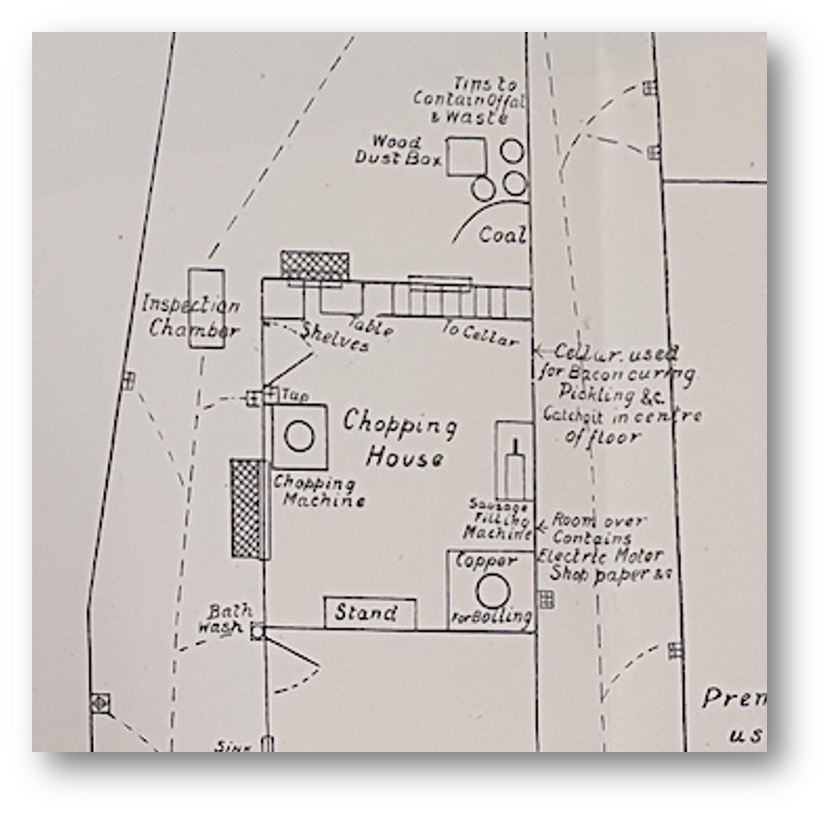

Derby’s food poisoning outbreak was traced back to Cope’s pork butchers in Iron Gate. A plan of the premises drawn by inspector F.W. Ford in 1902 can be found below. His premises extended approximately eighty yards from the main street and had a slaughterhouse attached to the back. As highlighted in the extract above, the outbreak was predominantly associated with pork pies purchased from Cope’s shop. However, illness was also caused by other pre-cooked food articles not mentioned in the source, such as chitterling (pig intestines).[2] Interestingly, many individuals relied on convenience foodstuffs during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as cooked meat and meat pies, due to meagre housing conditions, cooking facilities and lengthy working hours.[3] The particular foodstuff associated with the outbreak in Derby had been contaminated during the preparation process. Traditionally, gastric illnesses had been associated with specific foodstuffs rather than its preparation.[4]

The premises plan of Mr Cope’s Butchers. Produced and drawn by F.W. Ford in 1902 and was found in Howarth. Report on the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning, between pp. 20-21.

Furthermore, the extract above draws attention to Howarth’s role as MOH. During the nineteenth century, the responsibilities of the MOH extended as public health became medicalised. The Public Health Act of 1872 required sanitary authorities to appoint a MOH while the Public Health Act of 1875, required officers to be “legally qualified medical practitioners”.[5] As MOH for the Borough of Derby, Howarth requested information and advice from other officers and worked closely with Sheridan Delépine and other inspectors to produce his report. Delépine, was a professor of bacteriology at Owens College, Manchester University. He produced a bacteriological investigation into Derby’s outbreak; his report was appended to Howarth’s document.

During Howarth’s initial enquiry, he believed that the meat could have caused the outbreak. Howarth’s suspicions are unsurprising as despite the deterioration of the ‘diseased’ meat trade following the Cattle Plague (mid-1860s) and more strict regulations such as the Food and Drugs Act of 1875, ‘bad’ meat remained a critical source of illness.[6] There had been a plethora of meat poisoning epidemics in Middlesbrough (1880 and 1881), Welbeck (1880), Nottingham (1881), Mansfield (1896) and Chadderton and Oldham (1898).[7] However, through Howarth’s investigation of the premises, he later claimed that the ‘flesh’ of the pigs used to make the pork pies were not the primary cause of the illness. Instead, he argued that the ingredients and utensils used to make the pies had been contaminated. Howarth and Delépine arrived at similar conclusions regarding the origin of the outbreak.[8] Delépine stated that the food articles had come into contact with faecal matter during preparation in the ‘Chopping House’; here, the meat was chopped and minced, and the jelly for the pork pies was produced.

Faecal contamination was, however, not uncommon. In 1894, Delépine had comparably concluded that excrement had polluted milk and had caused a similar outbreak of illness in Manchester.[9] Likewise, William Savage, Medical Officer for Colchester and, in 1909, the County of Somerset, stated: “all those familiar with the inspection of places where food is prepared…know that faecal contamination…must be very common”.[10] Consequently, this episode in Derby, like similar outbreaks elsewhere, emphasised the lack of precautionary action taken to prevent cross contamination on the premises alongside effective sanitary practices.

The food poisoning outbreak in Derby also sheds light on the role of respectability within urban society. Howarth suggests that the figures he reported on the number of ill individuals are underestimates. He believed that some individuals did not want to report their illness out of ‘sympathy’ for Mr Cope or fear of publicity. The notion of ‘respectability’ was extremely important within society and defined acceptable modes of behaviour. Historian Elizabeth Roberts argued that ‘respectability’ played a role in the lives of practically all working-class individuals in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries and regulated both class and gender identities.[11] Notably, the appearance of respectability was essential from an economic viewpoint. In times of adversity, the community could provide support, therefore, retaining the respect of neighbours, local business owners, and family was crucial. Despite this, Howarth’s failure to obtain more accurate statistics may have also been due to individuals dismissing their symptoms. Typically, gastric illnesses were common and often went unreported. Food poisoning was not made a compulsorily notifiable illness until 1939.[12]

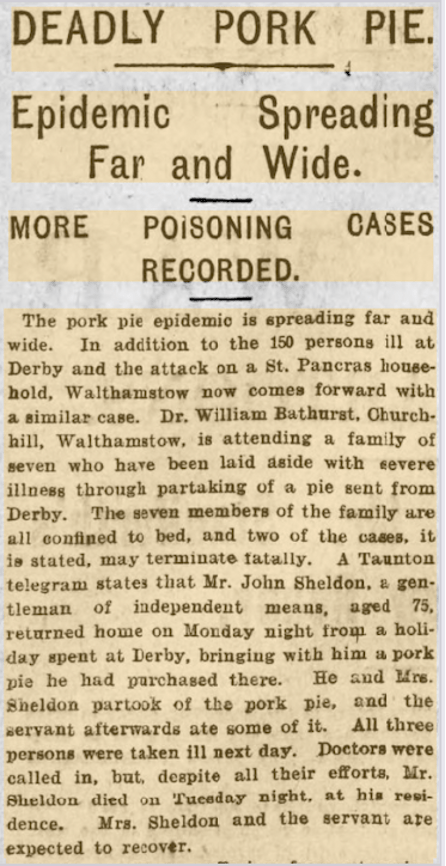

The outbreak draws attention to the movement of individuals in and out of Derby’s ‘slum’ region. Howarth stated that he was made aware of additional cases of illness outside of Derby from newspaper articles (see example-right). Cases were reported in Uttoxeter, Leeds and London (alongside other places).[13] There were approximately one-hundred-and-thirty-one cases of food poisoning in the Borough and ninety cases elsewhere. Four fatal cases were reported: two in Taunton, one in Sheffield and another in Uttoxeter. In many cases reported to Howarth, contaminated food articles were gifted to neighbours or employees. For the working class, meat consumption and diet remained closely linked to employment.[14] In the full report, Howarth discussed a ‘Mrs A’ who had stopped at Cope’s butchers while travelling to Duffield on the 4th September.[15] ‘Mrs A’, her family, and her stable boy consumed the pie and became ill. However, she also gifted the pie to ‘Mrs G’, who had come to complete housework; ‘Mrs G’ and her family also became unwell. The outbreak demonstrated how information and the pork pies travelled geographically and how neighbours or employees came to obtain the foodstuff.

The extract from Howarth’s report draws attention to his role as MOH and the connection between those involved in observing, examining, and ‘preventing’ illness in Derby. Due to Howarth’s investigation, Mr Cope was made to improve the general cleanliness of his premises while sanitising the building using limestone to reduce the likelihood of faecal contamination occurring again.[16] Notably, Howarth’s report maps the movement of Cope’s pies within and beyond Derby and highlights how individuals often came to obtain foodstuff from other community members. His report also underscores the importance of ‘respectability’, which prevented individuals from reporting their illnesses.

[1] Hardy, A., ‘Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory. A Short History of Food Poisoning in Britain, circa 1850-1950’, The Society for Social History of Medicine, 12.2 (1999), pg. 293; Waddington, K., The Dangerous Sausage’, Cultural and Social History, 8.1 (2011), pg. 51.

[2] Howarth. Report on the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning, pp. 18-19.

[3] Waddington. ‘The Dangerous Sausage’, pg. 56; Hardy. ‘Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory’, pg. 297.

[4] Hardy. ‘Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory’, pg. 296.

[5]Public Health Act 1875, Chapter 55 (published 11th August 1875). Available Online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/38-39/55/enacted [accessed: 9th January 2023]; Hardy. ‘Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory’, pg. 296.

[6]Sale of Food and Drugs Act 1875, Chapter 63 (published 11th August 1875). Available Online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1875/63/enacted#:~:text=No%20person%20shall%20sell%20any%20compound%20article%20of%20food%20or,penalty%20not%20exceeding%20twenty%20pounds [accessed: 9th January 2023]; Colins, E.J.T., ‘Food adulteration and food safety in Britain in the 19th and early 20th centuries’, Food Policy, 18.2 (1993), pg. 100.

[7] Colins. ‘Food adulteration and food safety in Britain in the 19th and early 20th centuries’, pg. 101.

[8] Howarth. Report on the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning, pp. 26-27, 35, 47.

[9] Delépine, S., ‘The Bearing of Outbreaks of Food Poisoning upon the Etiology of Epidemic Diarrhoea’, The Journal of Hygiene, 3.1 (1903), pp. 74-77.

[10] Savage, W.G., 1909 in Hardy. ‘Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory’, pg. 301.

[11] Mauriello, T.A., Working-class Women’s Diet and Pregnancy in the Long Nineteenth Century What Women Ate, Why, and its Effect On Their Health and Their Offspring (unpublished DPhil Thesis, University of Oxford, 2008), pp. 189-190.

[12] Hardy. ‘Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory’, pg. 309.

[13] Howarth. Report of the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning, pg. 14.

[14] Waddington. ‘The Dangerous Sausage’, pg. 54.

[15] Howarth. Report of the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning, pp. 15-16.

[16] Howarth. Report of the Recent Outbreak of Food Poisoning, pg. 34.