by Abie Waller

In the nineteenth century, much like today, the public house can be found at the centre of a community. The public house was a common institution within both rural and industrial areas and a recognisable location within most neighbourhoods.[1] Walker Lane was no different. As of 1897, there were four recorded public houses on this road, with similar data suggesting that this was a common theme throughout the nineteenth century.[2] The presence of such establishments suggest that they were a central component of community in areas faced by high levels of abject poverty.

“I went to the Hen and Chickens, but on enquiring found he was not there. I sat down and had several glasses of ale”

John Bostock, Derby Mercury, 1st April 1857

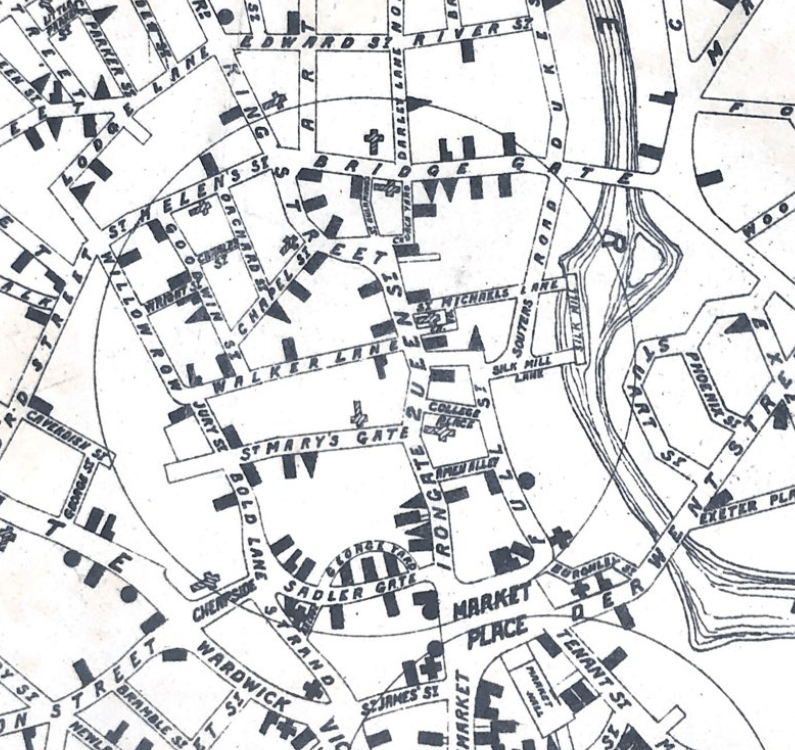

This map published by John Wills, an architect and surveyor, in 1897 highlights the areas in which ‘intoxicating drinks’ could be bought and consumed within Derby.[3] This map displays the prevalence of the public house and alcohol within the poverty-stricken areas of Derby during this period. Walker Lane is notable in this due to the area being highlighted on the map itself. As mentioned by Edward Cresy in his report to the General Board of Health, Walker Lane was a ‘street of some length’ and had ‘several Courts opening into it’.[4] The presence of both the public houses and the large number of inhabitants on the street highlight the way in which such establishments were key areas of community within the neighbourhood. These combined factors suggest that the public house was a key element and location in leisure pursuits of the working people living in industrial Derby.

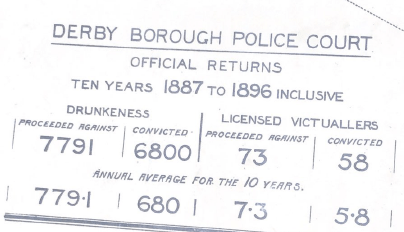

The map is rather interesting when considering the society it was created within. Aside from the physical representations of drinking establishments, the map includes statistics from the borough police court demonstrating the number of drunkenness cases between 1887 and 1896.[5] This suggests that the sentiment behind this map falls in line with that of the temperance movement prevalent in England at the time. Whilst this ethos, within the middle class especially, opposed the public house as a centre of community and leisure for the working classes,[6] it does fall in line with the tone of many newspaper reports that surrounded the dealings of public houses, including those on Walker Lane.

The nineteenth century saw a rising negativity towards the public house, especially in areas of poverty, such as Walker Lane.[7] Through the presence of newspapers, like the Derby Mercury, public houses such as the Hen and Chickens and the George and Dragon became known as centres of immorality and violence.[8] These narratives perpetuate the negative associations of the public house and overshadow the brighter communal aspects of their existence.

On one hand, pubs on Walker Lane were connected to some more violent aspects of crime in the area. In 1857 the Hen and Chickens featured in a violent robbery which the Derby Mercury entitled ‘Another Garotte Robbery in Derby’.[9] This crime was committed after the victim Mr John Bostock and the assailants left the Hen and Chickens and were travelling up Walker Lane. The Hen and Chickens then featured as the place of arrest for the assailants.[10] This newspaper report implies that public houses, like the Hen and Chickens, were the meeting grounds of petty and violent criminals.

“I then accompanied the police to the Hen and Chickens, and at one pointed out the prisoners […] who were amongst the company there”

John Bostock, Derby Mercury, 1st April 1857

However, even within this article there is evidence of the public house as a place of leisure and community. Bostock stated that although he went to the Hen and Chickens in search of his companion, he stayed for ‘several glasses of ale’.[11] The simpleness of this action demonstrates the way in which the public house was ingrained into the leisure time of people in the nineteenth century.

The Hen and Chickens (or sometimes known as the Old Hen and Chickens)and the George and Dragon (which sat on the corner of Walker Lane and Jury Street), were generally sites of more minor infringements of the law. Most references to the Hen and Chickens originate from newspaper and court reports that associate the location with nefarious deeds and illegal activity. Whilst this makes it difficult to consider the wider aspects of this public house and its relationship with the community as a whole, when looked at more closely many of these negative reports are relating to drunkenness and faulty publicans rather than extreme violence.

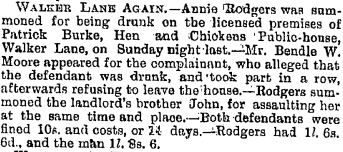

Some of the reports that focus on the general offenses include that by Annie Rodgers who was summoned to court for being drunk at the Hen and Chickens in 1896.[12] It can be surmised from this report that this is a regular occurrence as it is titled ‘Walker Lane Again’.[13] In this context, the connections between the poor, the public house and immoral behaviour become clear within in media. However, it is important in this instance is to remember that not only are newspapers generally tailored to middle class readership and sensibilities. Furthermore, there are many issues of the Derby Mercury where these instances do not appear. This means that it is possible to suggest that the public house had a greater role in positive community relationships than negative ones.

By exploring the public houses of Walker Lane, it presents the opportunity to understand aspects of leisure within areas of poverty which if often unwritten. When considering both the history of Walker Lane and poverty stricken areas more generally the public house gives an insight into the normalcy of people’s everyday lives.

[1] Hands T, Drinking in Victorian & Edwardian Britain: Beyond the Spectre of the Drunkard, (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018) p.1

[2] Wills J, Maps of the Boro of Derby shewing the number and position of Houses Licensed for the Sale of Intoxicating Drinks revised to January ; variety of news reports\

[3] Wills, John, Map of the Boro of Derby shewing the number and position of Houses Licensed for the Sale of Intoxicating Drinks, 1897, Derby Local Studies Library

[4] Cresy E, Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage and supply of water, and the sanitary conditions of the inhabitants of the Borough of Derby, 1849 p.13

[5] Wills, John, Map of the Boro of Derby shewing the number and position of Houses Licensed for the Sale of Intoxicating Drinks, 1897, Derby Local Studies Library

[6] Jackson W.J; Paterson A.S; Pong C.K.M; Scarparo S; Jeacle I, ‘”How easy can the barley brie”: Drinking culture and accounting failure at the end of the nineteenth century in Britain’, Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25.4 (2012) P.642

[7] Booth N, ‘Drinking and Domesticity: The Materiality of the Mid-Nineteenth-Century Provincial Pub’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 23.3 (2018) P.293

[8] Anon, ‘Derby Borough Police Courts’, Derby Mercury 8th July 1896 p.5; Anon, ‘Another Garrotte Robbery in Derby’, Derby Mercury 1st April 1857, p.6

[9] Anon, ‘Another Garrotte Robbery in Derby’, Derby Mercury 1st April 1857, p.6

[10] Anon, ‘Another Garrotte Robbery in Derby’, Derby Mercury 1st April 1857, p.6

[11] Anon, ‘Another Garrotte Robbery in Derby’, Derby Mercury 1st April 1857, p.6

[12] Anon, ‘Derby Borough Police Courts’, Derby Mercury 8th July 1896 p.5

[13] Anon, ‘Derby Borough Police Courts’, Derby Mercury 8th July 1896 p.5