by James Greenwood

Before the development of government support for the ill and unemployed, as well as widespread unionisation, the friendly society was important for working class lives. For these societies provided the often-vital economic aid to its members in times of need and or when the local Poor Law Relief was not enough. In 1843 members of the Ancient Order of Foresters met at the Joiner’s Arms Public House on St Helen’s Street to celebrate the establishment of the Order at St Helen’s Street.[1] The Order was only established in 1834 in Salford and therefore its expansion to Derby nine years later emphasises two things: Derby’s need for financial relief and popularity of friendly societies nationally.[2]

Friendly societies were not like the typical charitable and philanthropic organisations of the time, which were normally established and run by the middle classes, instead the societies were largely run by their members, the working class.[3] This is an important notion to mention as friendly societies and charity work more generally has been a focus of historians of the nineteenth century. Yet historians have usually looked at friendly societies as attempts by the working class to conform to middle class notions of respectability and discipline.[4] However, this notion, built upon notions of hegemony (the idea the dominant class in society dictates culture), should be criticised with friendly societies instead being a working-class movement of working-class values such as mutualism. This also links them to other working-class political movements such as trade unions and cooperatives.[5] Furthermore, the friendly society became incredibly popular in period, before the rise trade unions, with approximately five point eight million men in friendly societies by 1905.[6] They should also not be purely viewed in relation to middle-class values but as an independent effort of the working-classes to present themselves as respectable and self-disciplined. To this end, friendly societies were a dynamic force in society being shaped but also shaping notions such as respectability and self-discipline.

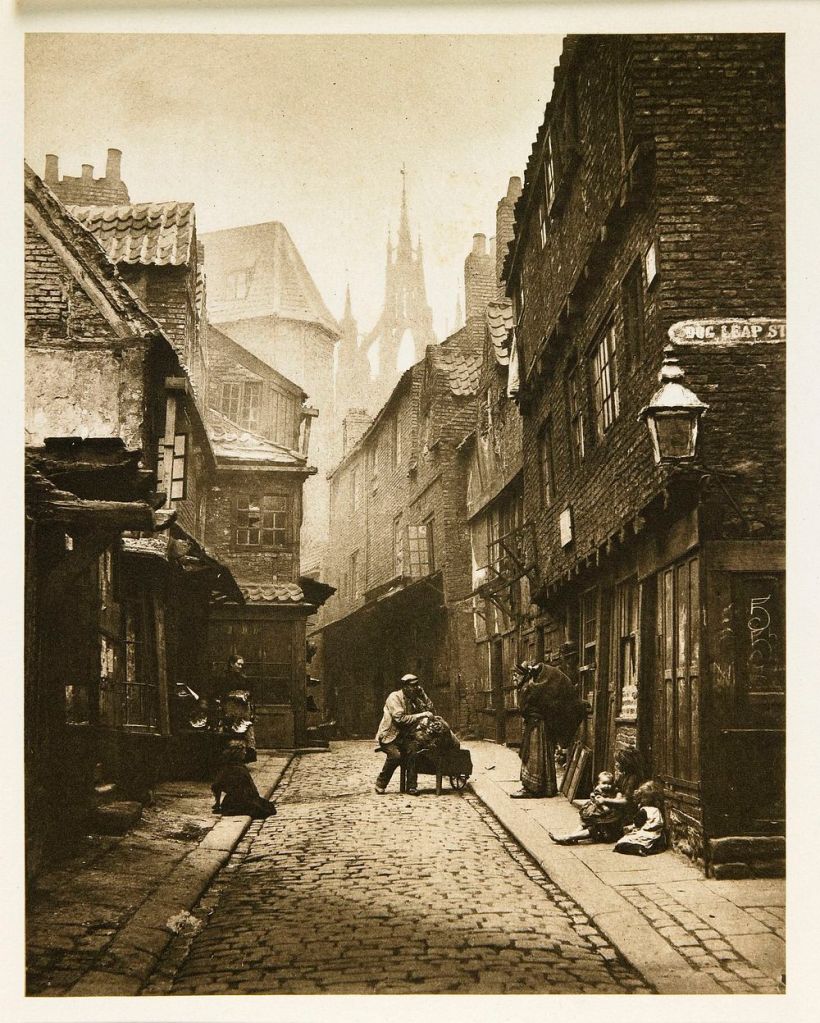

Respectability is an important notion to discuss when looking at friendly societies in the nineteenth century, especially in the context of St Helen’s Street which on the surface was seen to be a respectable street. Respectability was quite important in Victorian society as the historian Best calls it: “the great Victorian shibboleth and criterion”. Which means respectability was the method to judge people on their appearance and behaviour.[7] Whereas the historian Bailey argues it was not a cultural absolute but rather a dynamic and malleable concept.[8] Friendly societies seem to support Bailey’s claim as they enabled the working-classes to adopt the discussion around respectability and become respectable in the eyes of the middle-classes while still staying true to themselves. The historian Tholfsen’s argued that working-class members of friendly societies saw friendly societies as a conscious and responsible decision not to surrender to middle-class values.[9] Friendly societies were also framed to be patriotic and English, to further cement their respectability, with it being said friendly societies gave the ‘strong feeling of independence that an Englishman ought to feel’.[10] Therefore, these societies can be seen as a hard fought claim to collective respectability and freedom from middle-class interference for the working-classes.[11]

Despite the rhetoric of friendly societies seeking to be independent and free from middle-class interference it is important to note that the middle-class had a place in these societies too. While they were working class institutions middle-class people did interact with them and work with them, especially those of the lower middle class.[12] Furthermore, friendly societies enabled working-class people to entry public life, which was largely dominated by the middle-class, as they became respectable via their membership in these societies. Finally, following the enfranchisement of working men throughout the Victorian Period friendly societies also caught the attention of upper- and middle-class politicians who sought to cultivate support by interacting with friendly societies.[13] Hence, friendly societies despite being mostly working-class institutions were nuanced and were interacted with by middle and even upper-class people at various levels.

Yet friendly societies did not always achieve their aims in making the working-class more respectable in the eyes of the middle-class. Within popular working-class culture, the publican was incredibly important and well trusted by the community and as such the public house was very intertwined with friendly societies in the period.[14] For the working-class the public house was one of the few places available and affordable for friendly societies to meet.[15] This was also the case on St Helen’s Street with the Ancient Order of Foresters establishing themselves in the Joiners Arms.[16]

However, this conflicted with the middle-class’ ideas around respectability which in the Victorian period was closely associated with the middle-class ideas of temperance.[17] Furthermore, there was a reformist working class culture which aligned more closely to middle-class notions of respectability which can be seen with chartist movements integrating teetotalism for example.[18] On the other hand respectability was not one cohesive force in Victorian society but rather a changing concept which differed from people to people so much so it was not even cohesive throughout the middle-class.[19] To this end it would be hard to argue that the friendly society did not improve the ‘respectability’ of working-class members in some capacity despite their relation to public houses and drinking. Simply because financial stability and independence from middle-class aid would have carried enough weight in the ongoing dialogue, of the time, about respectability.

In conclusion, the arrival of Ancient Order of Foresters to St Helens Street in 1843 and its mention in the Derby Mercury says a lot about Victorian Britain and the slums of Derby. It shows how widespread the friendly society was in Victorian Britain when a Salford founded organisation made its way to Derby so quickly after its founding. It enables the discussion about Victorian and Edwardian respectability and how the friendly society was involved in this discourse between the working- and middle-classes, especially given St Helen’s Street’s position as a meeting point between the working and middle-classes. Finally, it shows the importance of the friendly society not just economically but also its importance for working-class community and culture in a middle-class dominated world.

[1] “WEDNESDAY, APRIL 19, 1843.” Derby Mercury, 19 Apr. 1843. British Library Newspapers.

[2] Foresters Friendly Society, ‘About Us – Our History’. Available Online https://www.forestersfriendlysociety.co.uk/about-us/our-history/ Date accessed: 6th December 2023

[3] Prom, Christopher J. “Friendly Society Discipline and Charity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian England.” The Historian (Kingston), vol. 72, no. 4, 2010, p. 888.

[4] Prom, Christopher J. “Friendly Society Discipline and Charity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian England.”, pp. 888–908;

Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 34, no. 1, 1995, pp. 35–58.

[5] Prom, Christopher J. “Friendly Society Discipline and Charity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian England.”, p. 904.

[6] Prom, Christopher J. “Friendly Society Discipline and Charity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian England.”, p. 889.

[7] Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 34, no. 1, 1995, p. 37.

[8] Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.”, p. 39.

[9] Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.”, p. 41.

[10] Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.”, p. 46, P. 53.

[11] Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.”, p. 58.

[12] Prom, Christopher J. “Friendly Society Discipline and Charity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian England.”, p. 889.

[13] Prom, Christopher J. “Friendly Society Discipline and Charity in Late-Victorian and Edwardian England.”, p. 908.

[14] Beaven, Brad. Leisure, Citizenship and Working-Class Men in Britain, 1850-1940, Manchester University Press, 2005. p. 65.

[15] Cordery, Simon. “Friendly Societies and the Discourse of Respectability in Britain, 1825-1875.”, p. 51.

[16] “WEDNESDAY, APRIL 19, 1843.” Derby Mercury, 19 Apr. 1843. British Library Newspapers.

[17] Beaven, Brad. Leisure, Citizenship and Working-Class Men in Britain, 1850-1940, p. 68.

[18] Huggins, Mike. “Exploring the Backstage of Victorian Respectability.” Journal of Victorian Culture : JVC, vol. 22, no. 1, 2017, p. 82;

Beaven, Brad. Leisure, Citizenship and Working-Class Men in Britain, 1850-1940, p. 67.

[19] Huggins, Mike. “Exploring the Backstage of Victorian Respectability.” Journal of Victorian Culture : JVC, vol. 22, no. 1, 2017, pp. 81–88