by Jordan Carr

On Wednesday 11th January 1854, the Derby Mercury had reported on a peculiar meeting in the Derby Guildhall concerning the Local Board of Health and the Board of Guardians. It was during this meeting that a Mr John Richardson had challenged the Board of Guardians over a nuisance emanating from the premises one of the Board’s own members – an Alderman by the name of a Mr John Sandars.

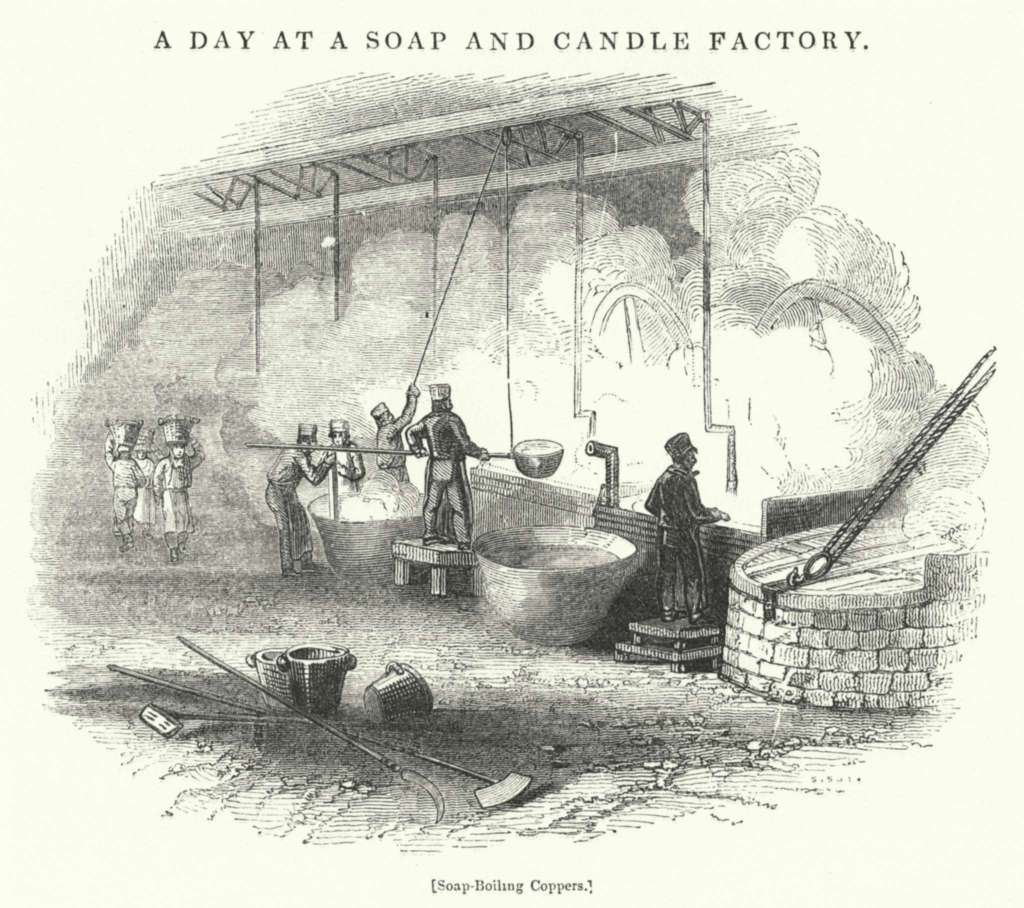

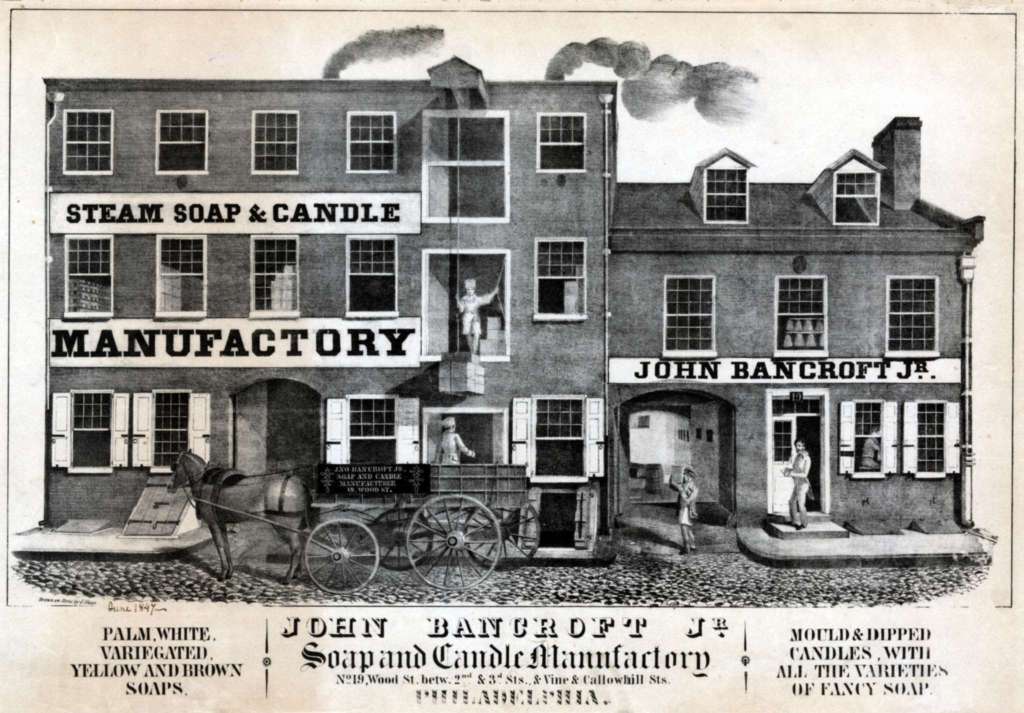

Mr Sandars was the owner of a soap manufactory on Bridge Street, Derby and it was from this property that a ‘one of the greatest nuisances’ or ‘stinks’ came from.[1] During this period, a nuisance was defined as something that is annoying and offensive to a person or a community’s senses – anything which effects the eyes, ears, and nose.[2] Indeed, this report includes one of those senses. It was a great smell that brought together the themes of nuisance inspections, corruption and harmful (or beneficial) odours to the noses of those residents living on or around Bridge Street.

This case study of Bridge Street shows that narratives of public health matters were complex and multilayered. The narratives of nuisance, smell, inspections, and corruption were not only shaped by inspectors and Alderman, but the views of Bridge Street residents and the Derby Mercury itself were instrumental in driving these narratives.

Firstly, it becomes clear in the report that there is a tension between issues over central government and the local authority. An inspector by the name of Mr Hanson is present at the meeting. He confirms that he had received complaints about the smell on Bridge Street, but he did not inform the committee. Mr Hanson was called before the Board of Guardians and according to the Derby Mercury his answer was that ‘it could not be remedied’ and he had looked at Government legislation to confirm this. Another member of the council, the Alderman Mr Barton replied that the inspector should have prioritized the committee over the Government legislation.[3] This is a short but noteworthy comment as it reflects a tension between the growing intrusiveness of the state in local matters. The inspectors’ comments and the contradiction expressed by Mr Barton supports the argument that a liberal culture of governance has an innate friction between the central and local government.[4]

Despite this, the inspector himself was challenged, whilst the Mr Sandars had to contend with remarks about the smell from residents. Christopher Hamlin mentions inspectors were regularly assumed to be ‘picking on the powerless’ and that they ‘insinuated corruption’.[5] This case can be seen to challenge that idea of powerlessness, as voices from below give agency to the residents in and around Bridge Street. The challenge comes from supposed quotes referring to the smell on Bridge Street, with a mixture of positive and negative attitudes.

The paper does not state specifically which residents gave their opinions, so one must exercise caution. However, those who did experience the smell of the soap factory must have lived on Bridge Street and the adjoining ones such as Brook Street and Agard Street.

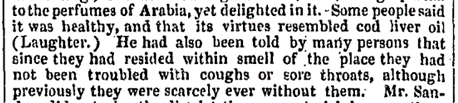

Secondly, the difference in descriptions of the smell shows the importance of public attitudes in providing community standards on health matters. For some residents the smell was described as ‘odoriferous’ and ‘nauseating’, whilst others were said to have described the smell as healthy, likening it to ‘cod liver oil’ and the ‘perfumes of Arabia’.[6] The fact that these opinions were put forward shows the extent to which attitudes of smell and nuisance were driven by local complaint.

However, it also shows the limitations of the supposed era of liberal governance. There are no names put next to the different opinions of the smell. It has been pointed out that public participation in inspection processes could contain as much falsity as accuracy. Tom Crook notes that many complaints from tenants were anonymous due landlords warning them against making complaints.[7]

This shows that liberal governance was multilayered as the ability to make complaints anonymously took power away from Mr Sandars, but we get no names of the residents. It is a mixture of bottom-up, top-down, and sideways approaches to power relations. The threat of nuisance and the discussion of moving Mr Sandars soap factory away from the town can be seen to be an instrumentalization of nuisance to be a threat from below.

As mentioned, there were contradictory opinions on the Bridge Street smell ranging from its nauseating effect to its healthy qualities. Again, this shows the importance of residents, particularly the aspect of individual agency. These views are challenging the theory of effluvia or ‘Miasma theory’, which was the predominant belief of disease transmission during the mid nineteenth century. This theory maintains that the atmosphere could affect an individual’s health and thus disease and illness arose from foul smells or ‘bad air’.[8]

Despite this view, some people had claimed that the smell had abated any threat of illness. The paper mentions that since the smell appeared some people had not suffered from ‘coughs or sore throats’ despite it previously being a common occurrence.[9] This is the complete opposite view of Miasma Theory and presents Bridge Street as a place of many characters who were vital in driving narratives of public health.

Lastly, Mr John Richardson implies that the Board of Guardians may be corruptive in nature since they failed to spot a nuisance relating to one of their own members. Mr Richardson does not use the word ‘corruption’ but he does accuse the Board of a ‘great partiality’.[10] On top of the attitudes towards the smell, local residents could read about the inspection process and scrutinization of the Board of Guardians in the Derby Mercury. During this period other newspapers such as the Manchester Press, London Dailies and other periodicals were seen to portray themselves as ‘the guardians and definers of public standards’.[11] Moreover, this is an example of the press acting as a driver of institutional scrutiny or change. This report can inform discussions over the influence of press on public opinion and its ability to include people in a ‘political nation’.[12] The Derby Mercury was a local newspaper that not only gave a voice to those who had to live on Bridge Street, but it gave them a way to read about its progress and possibly create a sense of trust in public health matters.

The themes of nuisance inspections, smell, and corruption open news ways of exploring social history in Derby. The views of residents were disseminated in the local newspaper as well as between nuisance inspectors and Alderman, thus, showing them as participants in a liberal culture of governance.

References

[1] Anon., ‘Local Board of Health’ Derby Mercury, Derby, Issue 3247, January 11, 1854, p.8. Available online: British Library Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.derby.ac.uk/apps/doc/BA3200011499/BNCN?u=derby&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=a02d2fcc. Accessed online: 10 November 2023.

[2] Otter, Chris. The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800-1910 (London: University of Chicago Press, 2008), pp.99-106.

[3] Anon., ‘Local Board of Health’ Derby Mercury, Derby, Issue 3247, January 11, 1854, p.8. Available online: British Library Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.derby.ac.uk/apps/doc/BA3200011499/BNCN?u=derby&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=a02d2fcc. Accessed online: 10 November 2023.

[4] Crook, Tom., ‘Sanitary Inspection and the Public Sphere in Late Victorian and Edwardian Britain: A Case Study in Liberal Governance’ Social History 32.4 (2007), p.371.

[5] Hamlin, Christopher., ‘Nuisances and Community in Mid-Victorian England: The Attraction of Inspections’ Social History 38.3 (2013), pp.346-355.

[6] Anon., ‘Local Board of Health’ Derby Mercury, Derby, Issue 3247, January 11, 1854, p.8. Available online: British Library Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.derby.ac.uk/apps/doc/BA3200011499/BNCN?u=derby&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=a02d2fcc. Accessed online: 10 November 2023.

[7] Crook, ‘Sanitary Inspection and the Public Sphere’, pp.389-390.

[8] Wohl, Anthony S. Endangered Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain (London: J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd, 1983), pp.87-88.

[9] Anon., ‘Local Board of Health’ Derby Mercury, Derby, Issue 3247, January 11, 1854, p.8. Available online: British Library Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.derby.ac.uk/apps/doc/BA3200011499/BNCN?u=derby&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=a02d2fcc. Accessed online: 10 November 2023.

[10] Anon., ‘Local Board of Health’ Derby Mercury, Derby, Issue 3247, January 11, 1854, p.8. Available online: British Library Newspapers, https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.derby.ac.uk/apps/doc/BA3200011499/BNCN?u=derby&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=a02d2fcc. Accessed online: 10 November 2023.

[11] Garrard, John. ‘Chapter 2: Scandals: A Tentative Overview’ in Moore, James and John Smith (eds.) Corruption in Urban Politics and Society, Britain 1780-1950 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), p.34.

[12] Hampton, Mark. Visions of Press in Britain, 1850-1950 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004), pp.5-9.