Charlotte Baines

Uttoxeter Road Cemetery was founded in 1843[2], and Nottingham Road Cemetery was opened in 1855[3].

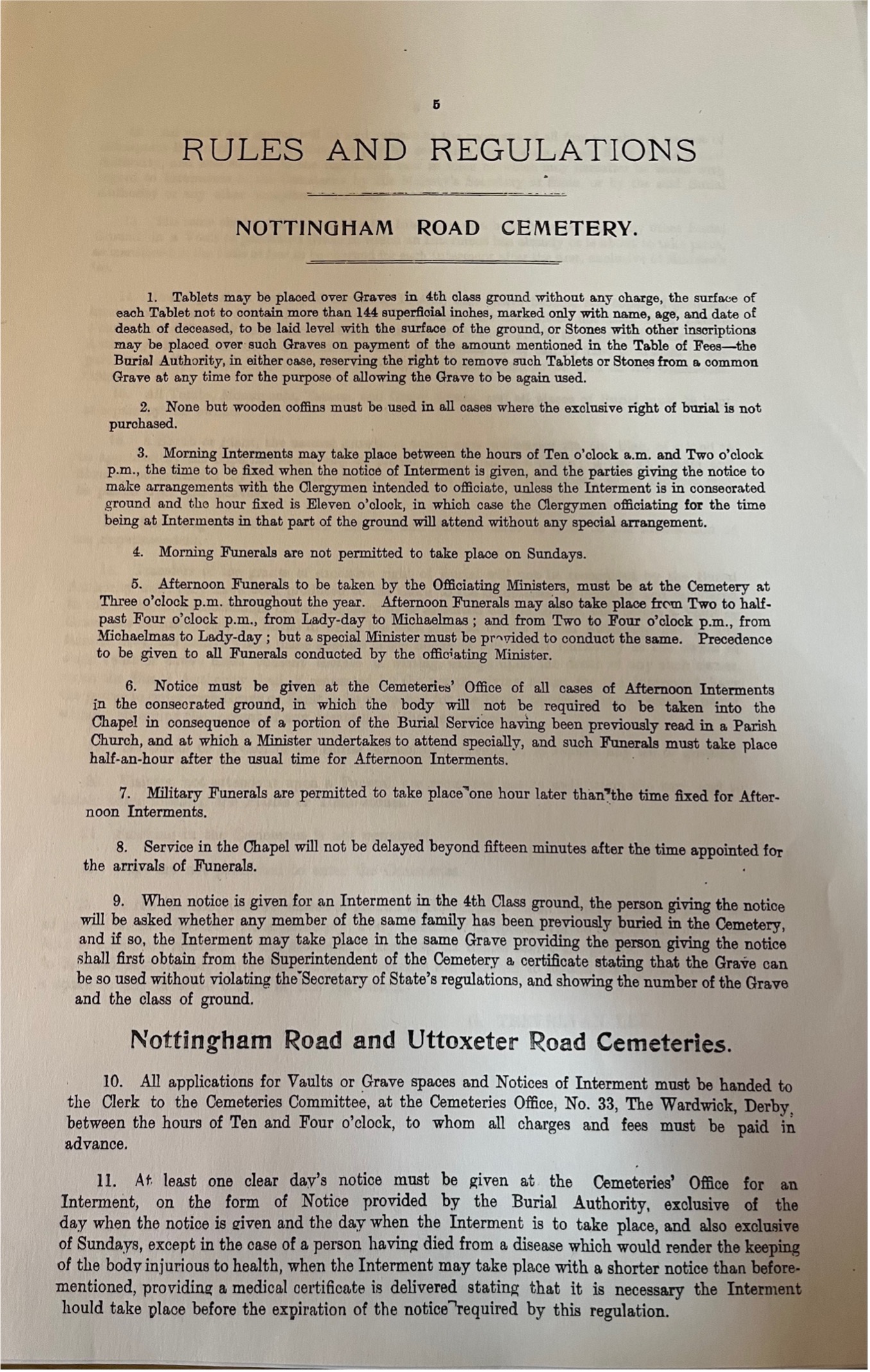

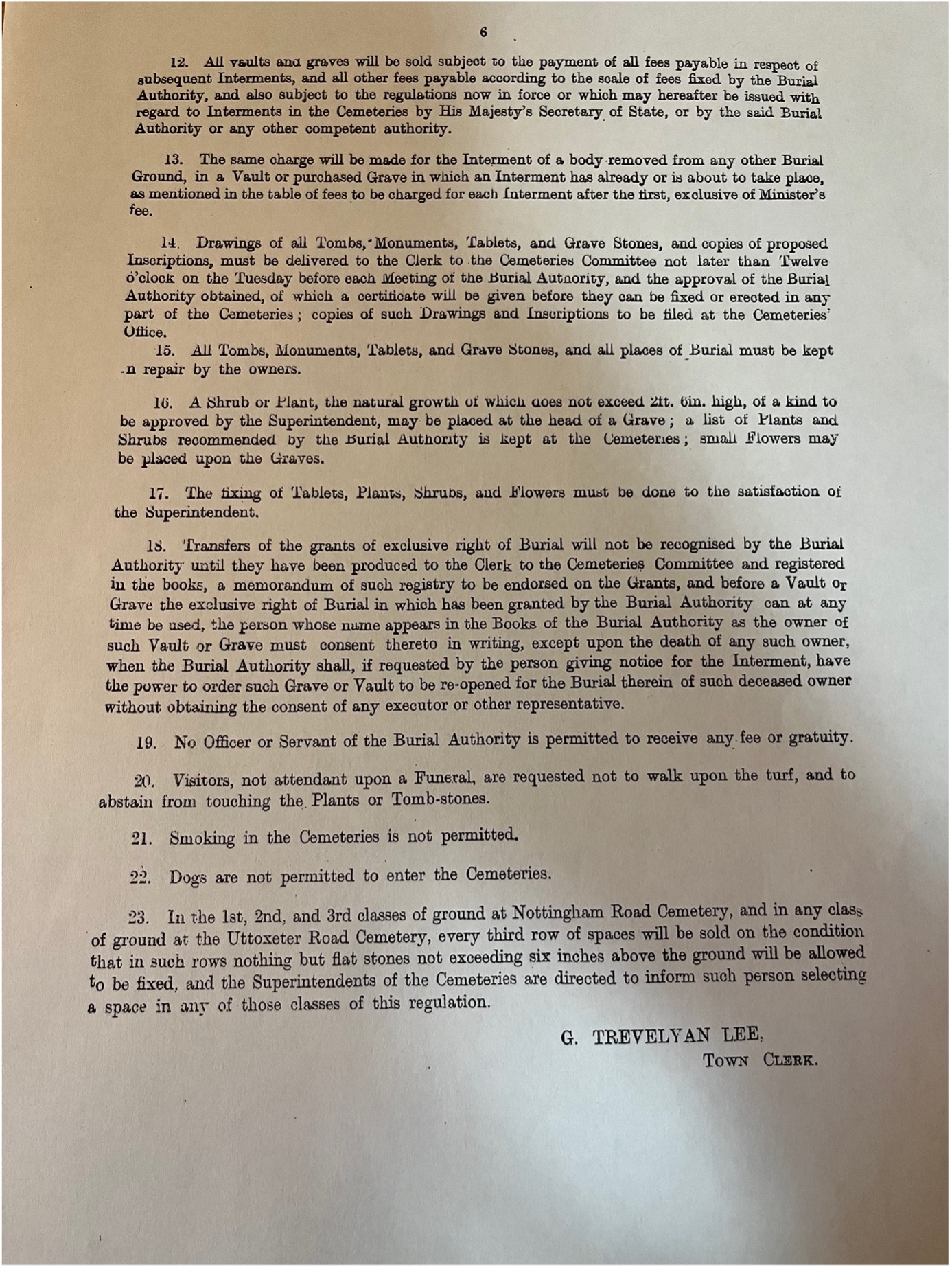

The title and subtitle of the source: ‘Rules and Regulations’ of ‘Nottingham Road Cemetery’ and ‘Nottingham Road and Uttoxeter Road Cemeteries’ suggests that burials and burial grounds in the 20th century went through a process of professionalisation and standardisation[4]. The source concerns the local administration of the two stipulated cemeteries[5], this means that the source concerns the social history of Derby[6]. Prior to the publication of the source ‘urban English cemeteries were places to avoid’ because of their unhygienic condition[7]. However, by the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, burials and burial grounds represented ‘moral consumption and aesthetic appreciations’[8]. The process of how this level of standardisation developed through the infliction of rules and regulations will be explored.

It is important to reflect on the process which led to the formation of a source because history, as a discipline, is centred on the idea that events interconnect as part of a process[9], therefore it is advantageous that the sources publication date is known: 1912[10]. This provides rational for analysing sources.

Throughout the 18th and 19th ‘centuries scientific understanding’ began to be applied to the ‘process’ of stipulating the requirements ‘of an ideal sanitary grave’[11]. These specifications can be implied from the ‘Rules and Regulations’[12], as they underpin the methodology for achieving an aesthetically pleasing cemetery. ‘Rules and Regulations’ propose the idea that burials and burial grounds became systematic events and places centred around an ideology of professionalism[13]. This suggests that policies caused the emergence of regulated processes and industry centred on burials and burial grounds.

The ‘Rules and Regulations’ place emphasis on the economic implications of death[14]. Financial centralisation is prominent within the source as there are numerous references to ‘fees’[15]. Historians, such as Nash[16], have argued that in the 19th century a cemetery was a ‘commercial’ institution that placed ‘consumer culture’ at the centre of its development[17]. This argument was articulated on the basis that the catalyst for cemetery construction was the progression of urban society[18]. This suggests that the construction of cemeteries was a socio-economic development, based on the process of capital professionalism. This analysis can also be drawn from the argument that cemeteries, in the 19th and 20th centuries, represented an ‘economy of death’[19]. This demonstrates that the cemetery became a product of consumption and, therefore, became commercialised. Therefore, analysing the source allows for the argument that cemeteries were economic developments.

However, some aspects of moral consumption are identifiable from the source[20]. The source allows a reader to assume that a ‘4th class ground’ is defined as a ‘common grave’[21]. Strange proposes that throughout the majority of the 19th century to be buried in a common grave ‘comprised the dignity of the dead’[22]. This is because a person’s social status was represented by the burial plot that they acquired[23] The wealthier classes tended to purchase private burial plots[24], whereas the poor were often buried in common graves[25]. This identifies that politics of poverty was prominent within burial grounds.

A common grave had no way of remembering those who had been buried within in it[26]. However, by the end of the 19th century public opinion became more inclusive towards those who experienced poverty[27]. ‘Burial Boards’ were encouraged to support ‘the memorialisation’ of the poor[28]. This can be identified from the source, as identity plaques could ‘be placed over Graves in 4th class ground without any charge’[29]. This suggests that there was empathy towards the poor and a desire to allow people to inclusively grieve for and respect the dead. However, this identification method was unable to truly be personalised, as it was regulated by the cemetery authorities[30], and plaques of identification could be removed from a common grave by burial authorities if the grave was required to be reutilised or if the identity stones became unkempt[31]. This identifies socio-economic repression, whilst representing the ideology of standardisation. Furthermore, the mention of the lower social classes suggests that the source was an inclusive document, representative of all social hierarchies[32]. This suggests that the politics of poverty became less repressive by the 20th century. This demonstrates how methods of memorialisation were regulated within cemeteries[33].

‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations (1912) pp. 5-6.

The source suggests that ‘Nottingham Road and Uttoxeter Road Cemeteries’ were expected to be aesthetically pleasing[34]. The source dictates that ‘the fixing of Tablets, Plants, Shrubs and Flowers, must be done to the satisfaction of the Superintendent’[35], whilst ‘a Shrub or Plant’ placed on a grave had ‘to be approved by the Superintendent’[36]. Planted vegetation was expected to be grown in a regimented way[37]. These rules stem from those formulated by Edwin Chadwick in 1843[38]. Chadwick proposed that people must ‘keep all the flowers, borders, and shrubs in the neatest order’[39]. Chadwick’s report was based on recommendations of changes that should be made in London[40]. Since the recommendations then progressed to be imposed onto Derby cemeteries, it can be suggested that burial grounds went through a process of standardisation, to be deemed aesthetically pleasing.

However, despite the regulations imposing nature to be ordered within cemeteries, it must be acknowledged that there was some opposition. Hart argued that natures natural vegetation would purities burial grounds[41]. This suggests that floristry designs should not have been regulated within burial grounds and would have been more efficient if they had been allowed to grow freely. Nevertheless, the control over nature demonstrates the level of standardisation within burial grounds, which offers a sense of professionalisation, draw from aesthetic appreciations. This provides historical context for what may have influenced the content of the ‘Rules and Regulations’ for ‘Nottingham Road and Uttoxeter Road Cemeteries’[42].

Overall, the ‘Rules and Regulations’ of ‘Nottingham Road Cemetery’ and ‘Nottingham Road and Uttoxeter Road Cemeteries’ caused the burial grounds to develop into aesthetically pleasing places through methods of standardisation that regulated how people used floristry to decorate the graves of the deceased[43]. The ‘Rules and Regulations’ also encouraged the memorialisation of all social classes[44], which shows how society became more socially inclusive in the 20th century compared to the 19th century. However, the commercialisation of burial grounds did cause there to be economic implications for those who desired to purchase a burial plot[45]. This demonstrates how the politics of poverty in Britain were prominent in burials and burial grounds.

[1] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations (1912) pp. 5-6.

[2] Derbyshire County Council, Derbyshire Record Office and Derby Diocesan Records Office: Cemetery Records (2009). <https://www.derbyshire.gov.uk/site-elements/documents/pdf/leisure/record-office/cemetery-records-guide.pdf> [Accessed: 28th December 2022].

[3] Derbyshire County Council, Derbyshire Record Office and Derby Diocesan Records Office: Cemetery Records.

[4] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations (1912) pp. 5-6.

[5] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[6] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[7] Walvin, J., ‘Dust to Dust: Celebrations of Death in Victorian England’, Historical Reflections 9.3 (1982), pp. 3563-371, p. 353.

[8] Strange, J-M., ‘‘Tho’ Lost to Sight, to Memory Over’: Pragmatism, Sentimentality and Working Class Attitudes towards the Grave, c. 1875-1914’, Morality 8.2 (2003), pp. 144-159, p. 152.

[9] Tosh, J., The Pursuit of History: Aims, Methods and New Directions in the Study of History, 6th ed. (Oxon: Routledge, 2015), p. 125.

[10] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[11] Rugg, J., ‘Constructing the Grave: Competing Burial Ideals in Nineteenth Century Britain’, Social History 38.3 (2013), pp. 328-345, p. 328.

[12] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[13] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[14] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[15] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[16] Nash, G. in Graves-Brown, P. M. (2000), cited in Rugg, J., Stirling, F. and Clayden, A., ‘Churchyard and Cemetery in an English Industrial City: Sheffield, 1740-1900’, Urban History 41.4 (2014), pp. 627-646.

[17] Nash, G. in Graves-Brown, P. M. (2000), cited in Rugg, J., Stirling, F. and Clayden, A., ‘Churchyard and Cemetery in an English Industrial City: Sheffield, 1740-1900’, p. 631-632.

[18] Rugg, J., Stirling, F. and Clayden, A., ‘Churchyard and Cemetery in an English Industrial City: Sheffield, 1740-1900’.

[19] Johnson, P. (2012), cited in Rugg, J., Stirling, F. and Clayden, A., ‘Churchyard and Cemetery in an English Industrial City: Sheffield, 1740-1900’.

[20] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[21] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[22] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’, Past & Present 178 (2003), pp. 148-175, p. 159.

[23] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’.

[24] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’.

[25] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’.

[26] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’.

[27] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’.

[28] Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’.

[29] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[30] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[31] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[32] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[33] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[34] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[35] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[36] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[37] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[38] Chadwick, E., An edition of Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain: A Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns. Made at the Request of Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department (1843) (2007) <https://archive.org/details/reportonsanitary00chaduoft/mode/1up?ref=ol&view=theater> [Accessed 17th December 2022].

[39] Chadwick, E., An edition of Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain: A Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns. Made at the Request of Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department (1843), p. 210

[40] Chadwick, E., An edition of Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain: A Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns. Made at the Request of Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department (1843).

[41] The Times (1884) cited in Thormsheim, P., ‘The Corpse in the Garden: burial, Health, and the Environment in Nineteenth-Century London’, Environmental History 16.1 (2011), pp. 38-68.

[42] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[43] Lee, G. T.,‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[44] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

[45] Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations.

Reference List:

Chadwick, E., An edition of Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain: A Supplementary Report on the Results of a Special Inquiry into the Practice of Interment in Towns. Made at the Request of Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department (1843) (2007) <https://archive.org/details/reportonsanitary00chaduoft/mode/1up?ref=ol&view=theater> [Accessed 17th December 2022].

Derbyshire County Council, Derbyshire Record Office and Derby Diocesan Records Office: Cemetery Records (2009). <https://www.derbyshire.gov.uk/site-elements/documents/pdf/leisure/record-office/cemetery-records-guide.pdf> Accessed 28th December 2022.

Lee, G. T., ‘Rules and Regulations’ in County Borough of Derby, Cemeteries: Fess and Regulations (1912) pp. 5-6.

Rugg, J., ‘Constructing the Grave: Competing Burial Ideals in Nineteenth Century Britain’, Social History 38.3 (2013), pp. 328-345.

Rugg, J., Stirling, F. and Clayden, A., ‘Churchyard and Cemetery in an English Industrial City: Sheffield, 1740-1900’, Urban History 41.4 (2014), pp. 627-646.

Strange, J-M., ‘Only a Pauper Whom Nobody Owns: Reassessing the Pauper Grave c. 1880-1914’, Past & Present 178 (2003), pp. 148-175.

Strange, J-M., ‘‘Tho’ Lost to Sight, to Memory Over’: Pragmatism, Sentimentality and Working Class Attitudes towards the Grave, c. 1875-1914’, Morality 8.2 (2003), pp. 144-159.

Thormsheim, P., ‘The Corpse in the Garden: burial, Health, and the Environment in Nineteenth-Century London’, Environmental History 16.1 (2011), pp. 38-68.

Tosh, J., The Pursuit of History: Aims, Methods and New Directions in the Study of History, 6th ed. (Oxon: Routledge, 2015).

Walvin, J., ‘Dust to Dust: Celebrations of Death in Victorian England’, Historical Reflections 9.3 (1982), pp. 3563-371.