Sanitation, sewage and water supply was a prevalent problem across all of nineteenth-century England and Wales, the need for the removal of sewage and clean accessible water underpinned the widespread of disease and the high death rate in slum areas.[1] Like poor nourishment, alcohol and drugs which all debilitated the body’s protection from disease and weakened the immune system, extremely low standards of hygiene and dirty water supply became a catalyst for disease and became an integral part in Victorian poverty and the lives of slum-dwellers.[2] In terraced houses water pumping was expensive and so extremely rare in poorer households and until the 1880s privies were usually on the ground level of terraced-houses and had often one WC shared between several different families and the entire household.[3] Medical Officers of Health (MOH) were appointed to provide a report of the generalised public health of England and Wales, documenting the medical advances that were to be taken in order to improve housing and sanitation such as, clean accessible water, sewage and drainage systems and improved housing conditions.[4] The Public Health Act 1872 mandatorily required that all sanitary districts appointed a MOH as a response to the increasing public health crisis.[5]

The deprived state of housing for the nineteenth-century urban poor meant that very few houses were equipped with the necessary drainage systems and many were without privies. It was not an uncommon occurrence for several hundred individuals to share a single outside tap for all of their water supplies as shown through the engraving in Figure 2.[6]

The engraving above was commissioned for The Illustrated Times in 1863 named “Queuing for Water” portraying a street plug in the slums of Bethnal Green. The reporters for the Illustrated Times were filled with desire to find out more about the poverty stricken poor within the East End of London. Upon entering the slums they were faced with the impoverished and dilapidated poor living in squalor and presented their findings on an engraving in order to display to the public the ever growing public health crisis and the desperate need for public health action.[7]

“It is not too much to affirm that no language permitted by ordinary delioaoy would adequately express the horrible condition of many of the letid courts and alleys in this district, where human beings are huddled together in the lowest stage of human wretchedness”[8]

In describing the slum area of Bethnal Green and reinforcing the engraving artwork the journalists for The Illustrated Times describe the penurious conditions in which the poor were forced to live. The representation of the slum dwellers in the engraving demonstrates the vital need for governmental intervention for clean water supplies, by the way in which people were forced to collect their water. The Illustrated Times also recorded the state of overcrowding in the houses of Bethnal Green by reporting on an attic in which ten persons resided. [9] For the majority of working-class families in the slums during the nineteenth century, the lack of running water in their houses inevitably led to long ques at local street pumps in all manners of foul weather, subsequently leading to vulnerable members of the community such as women and children drudging through mud and filth whilst carrying heavy equipment creating a significant physical burden upon them for sometimes up to and over a quarter of a mile.[10]

John William Tripe, M.D, the Medical Officer of Health for the district of Hackney in London constructed a report on the sanitary state of the district in 1856. Within his report he accounts the numerous occasions on which he discovered ‘filthy, badly drained’ streets permeated with ‘decaying vegetable matter’ and ‘overflowing with cess pools’. MOH John William Tripe under the Metropolis Local Management Act reported the aforementioned nuisances and the ‘offending parties’ were summoned to the Clerkenwell and Worship Street Police Courts. [11] In the MOH report for Croydon in 1893, the officer reports that the works on the sewage disposal for the specified area were ‘far from satisfactory’ and deemed so severe that a special report was required by the surveyor Mr. Chatterton, in order to provide appropriate recommendations to the authorities. He also states that in the unmentioned parishes drainage was, ‘disposed of in cesspools, and there is much too fear that the majority are not properly constructed’.[12] Six samples of water were taken from the Croydon District in 1893 and three were found to be unfit for drinking purposes. One was said to be ‘doubtful’ and the remainders were said to be ‘high in organic purity’. The only source of water for Coulsdon Common was derived from rainwater and ponds which were collected and stored in underground tanks, they were infested in ‘animalculæ’, visible to the naked eye. Due to the contaminated water supplies in Croydon there was notable levels of illness in the district, there was one fatal case of cholera in Mitcham and sixteen deaths from diarrhoea over the year.[13]

Death by Sewer

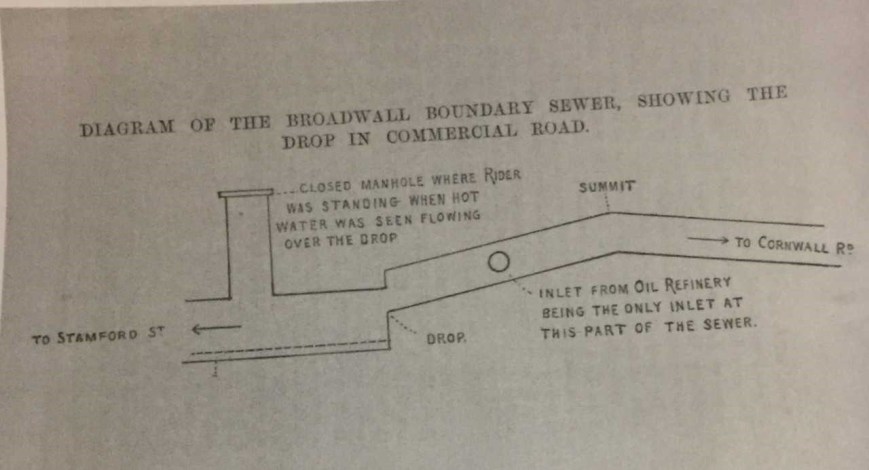

The role of the MOH was to pin point areas in need of public health reform.[14] The Victorian period was an era of poor drainage; drains were constructed with no comprehensive understanding of how to avoid ‘the flow-back of gases’. It was later in the period in the 1860s that fatal outbreaks of typhoid began to be connected to faulty sewage and drainage systems. [15] The MOH report of Lambeth in 1894 evidences that the ‘wretched state’ of the Broadwell Boundary sewer shown in Figure 3 was responsible for the accidental deaths of both William Garrod and Richard William Baker. A sample was taken from the sewer subsequently after the death of the two aforementioned men and it was found to contain, ‘admixture of sulphuretted hydrogen’. The residual sewage and inadequate ventilation of the Broadwell Boundary sewer produced sulphuretted hydrogen in an adequate magnitude to cause death.[16]

Inadequate drainage, sewage systems and poor water supplies were responsible for the deaths and illnesses of many of the impoverished poor in the Victorian period.[17] The Medical Officer of Health reports produced evidence in which the government could retain control and put preventative measures in place to eradicate the ever growing public health crisis in the nineteenth century. The MOH report in Hackney in 1856 and Croydon in 1839 demonstrates a clear link between drainage, water supply and illness.[18] Whilst the engraving in Figure 2 portrays the impoverished conditions of the working-class poor that the MOH were required to investigate. Lastly the lack of understanding in regards to competent drainage systems, evidenced by the fatalities in the Broadwell Boundary sewer in Lambeth reinforce the connection between illness, poor drainage and water supplies evidencing the importance of the role of the newly established Medical Officer of Health.[19]

[1] Rodger, R. Housing In Urban Britain, 1780-1914. Cambridge University Press, 1995 Page 44

[2] Wohl, S. A. Endangered Lives Public Health in Victorian Britain Methuen, 1984. Page 61

[3] Rodger, R. Housing In Urban Britain, 1780-1914. Cambridge University Press, 1995 Page 37

[4] Welcome Library. London’s Pulse: Medical Officer of Health reports 1848-1972 A new kind of medical professional (2018) Welcome Trust. Available at: https://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/about-the-reports/new-kind-of-medical-professional/ Accessed on: 04/11/2018

[5] Price, K. Medical Negligence in Victorian Britain – The Crisis of Care under the English Poor Law, c.1834-1900 (2015) London Page 67

[6] Flanders. J. Slums (2014) The British Library. Available at: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/slums Accessed on 04/11/2018

[7] Wohl, S, A. Endangered Lives – Public Health in Victorian Britain (Cambridge-University Press 1983) Page 62

[8] ‘The dwellings of the poor in Bethnal Green – The state of the water supply’ The Illustrated Times 24th October 1863. Available electronically: https://newspaperarchive.com/illustrated-times-oct-24-1863-p-9/ Accessed: 06/11/2018

[9] Dyos, H. J, and Wolff, M. The Victorian City. (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1976). Page 573

[10] Wohl, S, A. Endangered Lives – Public Health in Victorian Britain (Cambridge-University Press 1983) Page 62

[11] Trip, W. J “Report of Medical Officer of Health for Hackney” (1856) available online: http://welcomelibrary.org/item/b1988509x Accessed: 23/10/2018 Page 4

[12] “Report of Medical Officer of Health for Croydon” (1893) available online: http://welcomelibrary.org/item/b19786578 Accessed: 23/10/2018 Page 26

[13] “Report of Medical Officer of Health for Croydon” (1893) available online: http://welcomelibrary.org/item/b19786578 Accessed: 23/10/2018 Page 24

[14] Welcome Library. London’s Pulse: Medical Officer of Health reports 1848-1972 A new kind of medical professional (2018) Welcome Trust. Available at: https://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/about-the-reports/new-kind-of-medical-professional/ Accessed on: 06/11/2018

[15] Wohl, S, A. Endangered Lives – Public Health in Victorian Britain (Cambridge-University Press 1983) Page 102

[16] Verdon, W, H “The Annual Report on Vital and Sanitary Statistics” (1894) available online: https://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/report/b17998906#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 Accessed: 06/11/2018 Pages 44-48

[17] Rodger, R. Housing In Urban Britain, 1780-1914. Cambridge University Press, 1995 Page 44

[18] “Report of Medical Officer of Health for Croydon” (1893) available online: http://welcomelibrary.org/item/b19786578 Accessed: 23/10/2018 Page 24

[19] Verdon, W, H “The Annual Report on Vital and Sanitary Statistics” (1894) available online: https://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/report/b17998906#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 Accessed: 06/11/2018 Pages 44-48

Illustrations

Figure 1 – Punch, Or This London Charival, July 21 1855 Available online: https://londonhistorians.wordpress.com/tag/medicine/

Figure 2 -The dwellings of the poor in Bethnal Green – The state of the water supply’ The Illustrated Times 24th October 1863. Available electronically: https://newspaperarchive.com/illustrated-times-oct-24-1863-p-9/ Accessed: 06/11/2018

Figure 3 – Broadwell Boundary sewer 1800s, Imagine in: Verdon, W, H “The Annual Report on Vital and Sanitary Statistics” (1894) available online: https://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/report/b17998906#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 Accessed: 06/11/2018 Pages 44-48/2018