by Elexis Whittaker

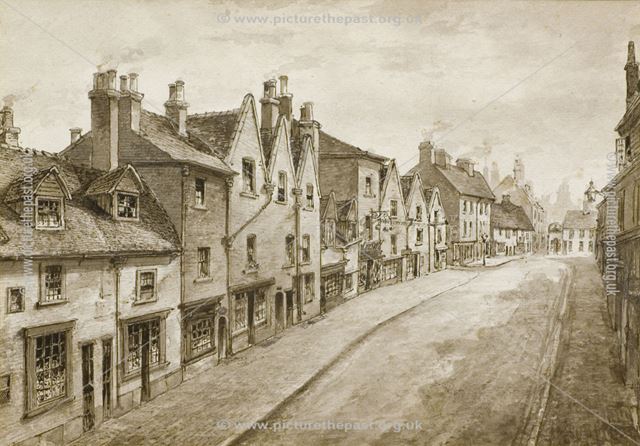

Willow Row in Derby had long been associated with slums, law-breaking, and crime. It received numerous complaints over the years. Drunkenness was the most common offense in Derbyshire at the beginning of the nineteenth century, with over 42 beer retailers scattered across Derby town centre[1]. For instance, in the 1850s, it was reported that Mary Ann Ford had repeatedly been warned about her drunken behaviour. On one occasion, Mary Ann Ford was arrested on Willow Row at three o’clock in the morning for shouting and kicking a police officer[2]. It came as no surprise that the county decided to establish a Gaol on Willow Row, as it was considered one of the worst areas for housing in Derby[3]. One can only imagine the levels of crime on this street alone.

The Three Derby Gaols

James Neild’s report in 1812 highlights the harsh conditions endured by prisoners in England, Scotland, and Wales[4]. His work documents the well-being and crimes of criminals, while also providing a comprehensive list of Borough Gaols across Britain. This report not only presents important data and a potential guide to prisons, but also gives Neild a platform to advocate for better living conditions for thousands of prisoners. Although primarily aimed at influencing parliamentary and penal laws, Neild’s use of qualitative data suggests that this work can also be used for academic purposes.

Neild’s language, such as his statement “To remedy this evil,”[5] clearly reflects his intention to address the injustice experienced by the lower classes at the hands of the legal system. One of Neild’s main concerns in his work is the imprisonment of individuals for minor offenses, such as debt, arguing that they would contribute more to society if given their freedom. In his comprehensive list of prisons and gaols on pages 61 to 64, he specifically mentions Derby County Gaol and House of Corrections.

[Fig.1] Willow Row 1880-1935 Available at: https://picturethepast.org.uk/image-library/image-details/poster/dmag300029/posterid/dmag300029.html

Firstly, Derby Borough Gaol was opened in 1756, and it was located on Willow Row. In 1818, the small local gaol housed 52 inmates throughout the year, a number that increased to 257 in 1828[6]. Both the Derby Gaol and the House of Corrections, situated across from each other, were notorious for their terrible conditions. The Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline report from May 1823 reveals that Willow Row Gaol lacked running water in one yard, and inmates received only half a loaf of bread per day[7]. Additionally, the Gaol had no matron, indicating a lack of medical care for the inmates. The majority of prisoners were convicted for debt, petty theft, or disturbances, which supports Neild’s observations on prison treatment.

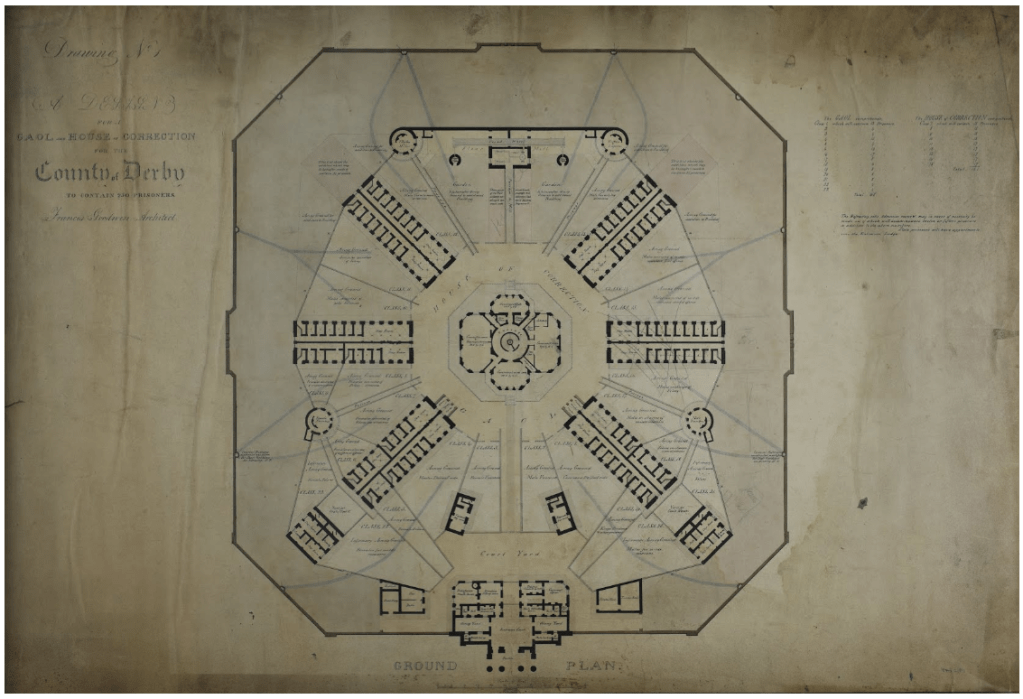

In 1825, both the Willow Row Gaol and House of Corrections relocated to Friar Gate[8]. It was reported that over 60 prisoners were housed in just seven cells. Similar to its predecessor, this new Gaol lacked medical facilities. Prior to the move, Friar Gate Gaol had witnessed 50 public and gruesome executions[9]. This included the public executions of John Brown, Thomas Jackson, George Boothe, and John King in 1817 for setting fire to hay and corn[10]. In the same year, Friar Gate Gaol was deemed inadequate and insecure after several inmates managed to escape. This prompted the planning of a new and larger Derby Gaol[11].

How Did They End Up There?

Secondly, alcohol-related violence has been a persistent issue in Derby, both in the past and present. As described in Harry Butterton’s book on Victorian Derby life, drunkenness was the most commonly charged offense in Derbyshire[12]. With over 127 taverns, pubs, and beer shops scattered throughout the streets of Derby, one can easily imagine the chaos that ensued outside their windows. In 1858, two regulars of a public house called Bishop Blaize, Arthur Bland, and Edwards, had been drinking since 11 am[13]. While one of the men had a criminal record, both were known for their violent tendencies. After consuming several drinks and engaging in multiple fights, the two men eventually fought each other, resulting in Bland fatally stabbing his opponent in the neck before medical assistance arrived[14].

Although this violence may appear senseless, understanding the living conditions and daily life in the slums of Derby sheds light on why the lower class would resort to such behaviour. In the 1870s, the Mercury newspaper detailed the horrors faced by the lower classes, particularly in the housing located at the end of Bold Lane on Willow Road[15]. The deplorable environment made it nearly impossible for the residents to lead clean and decent lives. For instance, one house on Willow Row had a gutter running through the bedroom, and the stench was so overpowering that windows and doors had to be constantly left open[16]. It is no wonder that the slum dwellers preferred spending their days and nights in taverns or pubs.

To conclude, the violence associated with alcohol consumption was incredibly prevalent in slum areas. Understanding the context of which these people lived helps reveal why these circumstances and behaviour existed. In the slums of England, such as those found in derby are trapped in a cycle of poverty and crime, the slum was characterised by neglect and indifference[17]. The lack of effective law enforcement led to high crime rates and the terrible living conditions endured by slum dwellers in Derby Gaols. This exposed the disturbing truth of how the higher classes perceived them. The harsh living conditions and the desperation to survive often drove individuals towards criminal behaviour.

References

[1] Butterton, H., & Gallery, A. (2006b). Victorian Derby: A portrait of life in a 19th-century manufacturing town. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL21362632M/VICTORIAN_DERBY_A_PORTRAIT_OF_LIFE_IN_A_19TH_CENTURY_MANUFACTURING_TOWN.

[2] Butterton, H., & Gallery, A. (2006b). Victorian Derby: A portrait of life in a 19th-century manufacturing town. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL21362632M/VICTORIAN_DERBY_A_PORTRAIT_OF_LIFE_IN_A_19TH_CENTURY_MANUFACTURING_TOWN.

[3] Butterton, H., & Gallery, A. (2006b). Victorian Derby: A portrait of life in a 19th-century manufacturing town. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL21362632M/VICTORIAN_DERBY_A_PORTRAIT_OF_LIFE_IN_A_19TH_CENTURY_MANUFACTURING_TOWN.

[4] Neild, James. “General List of Prisons Distinguished in Alphabetical Order.” The State of the Prisons of England, Scotland and Wales, John Nichols and Son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812, pp. 61–64.

[5] Neild, James. “General List of Prisons Distinguished in Alphabetical Order.” The State of the Prisons of England, Scotland and Wales, John Nichols and Son, Red Lion Passage, Fleet Street, 1812, pp. 61–64.

[6] Crime and Punishment – Derbyuncovered. (2023, October 7). Derbyuncovered. https://derbyuncovered.com/crime-and-punishment/ (accessed 14 December 2023)

[7] Crime and Punishment – Derbyuncovered. (2023, October 7). Derbyuncovered. https://derbyuncovered.com/crime-and-punishment/ (accessed 14 December 2023)

[8] Derby Borough Gaol – 19th century prison history. (2018, April 5). 19th Century Prison History. https://www.prisonhistory.org/prison/derby-borough-gaol/

[9] Crime and Punishment – Derbyuncovered. (2023, October 7). Derbyuncovered. https://derbyuncovered.com/crime-and-punishment/ (accessed 14 December 2023)

[10] Account of the life, trial & behaviour of John Brown, Thomas Jackson, George Booth, & John King ; who were executed on the new drop, in front of the county gaol, Derby, on Friday August 15, 1817. : For setting fire to hay and corn stacks. (n.d.). English Crime and Execution Broadsides – CURIOSity Digital Collections. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/crime-broadsides/catalog/46-990059386820203941

[11] Derby Borough Gaol – 19th century prison history. (2018, April 5). 19th Century Prison History. https://www.prisonhistory.org/prison/derby-borough-gaol/

[12] Butterton, H., & Gallery, A. (2006). Victorian Derby: A portrait of life in a 19th-century manufacturing town. [Link](https://openlibrary.org/books/OL21362632M/VICTORIAN_DERBY_A_PORTRAIT_OF_LIFE_IN_A_19TH_CENTURY_MANUFACTURING_TOWN)

[13] Lomax, S. (2012). Deadly Derbyshire: Tales of Murder & Manslaughter c.1700–1900. Grub Street Publishers.

[14] Lomax, S. (2012). Deadly Derbyshire: Tales of Murder & Manslaughter c.1700–1900. Grub Street Publishers.

[15] Butterton, H., & Gallery, A. (2006). Victorian Derby: A portrait of life in a 19th-century manufacturing town. [Link](https://openlibrary.org/books/OL21362632M/VICTORIAN_DERBY_A_PORTRAIT_OF_LIFE_IN_A_19TH_CENTURY_MANUFACTURING_TOWN)

[16] Butterton, H., & Gallery, A. (2006). Victorian Derby: A portrait of life in a 19th-century manufacturing town. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL21362632M/VICTORIAN_DERBY_A_PORTRAIT_OF_LIFE_IN_A_19TH_CENTURY_MANUFACTURING_TOWN.

[17] YOUNG, ARLENE. “Comprehending the Slum-Dweller: Affect and ‘A Child of the Jago.’” Victorian Review, vol. 40, no. 1, 2014, pp. 39–43, https://doi.org/10.1353/vcr.2014.0020.

Images used

Figure 1: Old Willow Row. (n.d.). Picture the Past. https://picturethepast.org.uk/image-library/image-details/poster/dmag300029/posterid/dmag300029.html

Figure 2: Design for a gaol and house of correction for the County of Derby – Francis Goodwin – Google Arts & Culture. (n.d.-b). Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/design-for-a-gaol-and-house-of-correction-for-the-county-of-derby-francis-goodwin/QgHixLPqW_lSOg?hl=en

Figure 3: Hawley, Z. (2020, June 14). Amazing photos show changing face of Derby landmark over three centuries. Derbyshire Live. https://www.derbytelegraph.co.uk/news/nostalgia/gallery/amazing-photos-show-changing-face-4223207