Edward Bradbury, ‘Half-Days in Derbyshire: Half-Days in Derby (continued)’, The Derby Mercury, 1st November 1899. Pp. 7

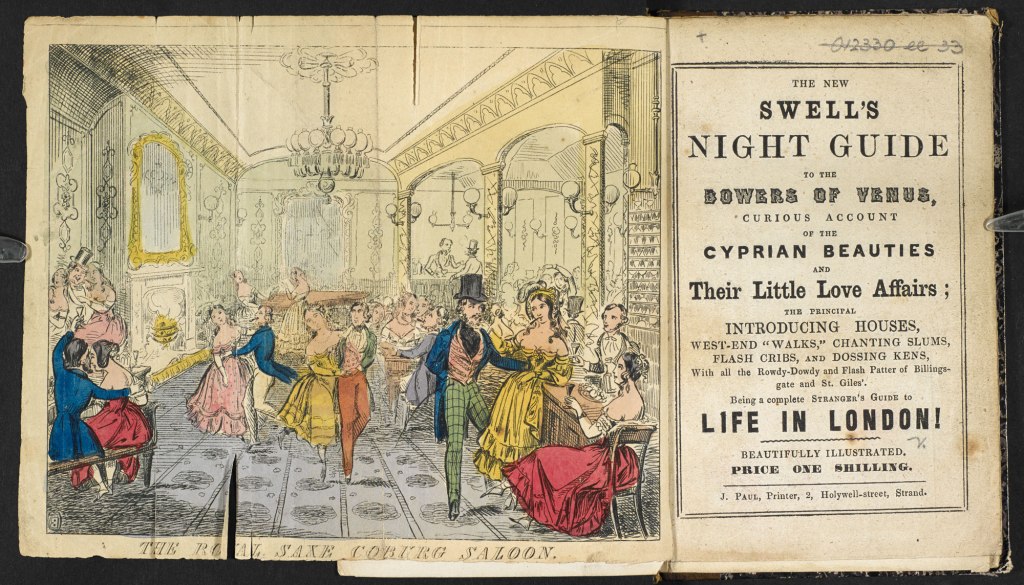

This newspaper article in The Derby Mercury from the 1st of November 1899 aims to depict Derby to an avid rambler. The Author, Edward Bradbury, wrote multiple travel literatures including Pictures of the Peaks.[1] In this article, Bradbury describes the loveliness of Derbyshire beauty spots, especially that of the Hardwick Hall estate. Later on in the article, the loveliness is completely flipped and becomes about the Derby Whitechapel, in reference to London’s Whitechapel area, a well-known poverty and crime-stricken area with the likes of Jack the Ripper roaming the streets. It is not unusual for guiding literature to do this, for example guide books from London not only included shops, theatres and monuments, but also places of philanthropic interests like Whitechapel and Shoreditch.[2] The audience of The Derby Mercury would have had a disposable income, with the paper costing 6d (around £1.95 in today’s money).[3] It is often argued that poorer people in England were illiterate, however 97.2% of men and 96.8% of women could read and write by 1900, so the only factor preventing slum dwellers from reading this newspaper article was the lack of a disposable income.[4] The article makes reference to criminality within the slums of Derby, with prostitution and brawls by ‘vicious men’ common-place. Drink and disorder within Derby’s slums are very clear here.

‘Here the prostitute prowls by night, and the pimp drinks by day’

Edward Bradbury, ‘Half-Days in Derbyshire: Half-Days in Derby (continued)’, The Derby Mercury, 1st November 1899. Pp. 7

In nineteenth-century London, the estimated number of prostitutes in the city was around 80,000 according to official documents. However, historians have claimed that at least half of these women were just deemed to be ‘whores’ by men for simply dressing and behaving a certain way or living in the same abode as a man.[5] Bradbury’s article places Derby’s prostitutes alongside Bess of Hardwick an ‘imperative woman who demanded noblemen to marry her’.[6] Although Bess of Hardwick was a Tudor Countess, the comparison made here creates a sense of the overworld and underworld that was present in Derby, an idea that was heightened by the middle and upper classes.[7] With this newspaper primarily being aimed at local inhabitants of Derby that tended to be from the middle and upper classes, this article definitely creates a sense of ‘us’ and ‘them’. The language of ‘vice’ and ‘misery’ amplifies this also.

The language depictions of Derby’s slums shows that the Walker Lane area was ‘unfit’, ‘unhealthy’, and ‘appalling’. This mirrors that of language surrounding the Whitechapel area of London’s East End. However, this did not prevent the middle and upper classes from engaging in ‘slum tourism’. In the first half of the nineteenth-century, slum tourism was guided by sincere concern for the welfare of the slum dwellers.[8] By the second half of the nineteenth-century, the slums became a place where middle and upper classes could spend their free leisure-time.[9] Exploring the slums of Derby, by using guides such as Bradbury’s, became another way to display how the middle and upper classes were ‘morally other’ from the slum dwellers. Of course, prostitution, brawling, and drunken disorder was not what the middle and upper classes deemed morally correct.

‘Where evil passions incite vicious men to black each other’s eyes and break each other’s heads’

Edward Bradbury, ‘Half-Days in Derbyshire: Half-Days in Derby (continued)’, The Derby Mercury, 1st November 1899. Pp. 7

In a modern sense, criminality within slums has always been a source of entertainment. Jack the Ripper has dominated period dramas and cinema with allegations and conspiracies flying around over who ‘he’ was. Even Madame Tussauds have a ‘Chamber of Horrors’ that depict Jack the Ripper as Aaron Kosminski a Polish barber that moved to London in the 1880s.[10] During the nineteenth-century, entertainment was no different.

It has been argued by historians like Bailey, Shore, and Philips that the criminal classes of the nineteenth-century were nothing more than a literary construction.[11] The Royal Commission on Penal Servitude in 1863 described the criminal classes as ‘a class of person… so inveterately addicted to dishonesty and so averse to labour that there is no chance of their ceasing to seek their existence by depredations on the public’.[12] These people were later referred to as ‘Garrotters’ with their lack of moral stamina to break from illegality.[13]

Bradbury’s article plays into the concept that criminal classes were just a literary construct as a form of entertainment for the middle and upper classes. Bradbury describes the vicious men that decide to black each other’s eyes and break each other’s heads as a way to greater increase the narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’ between ‘civilised’ society and the immorality of the slums.

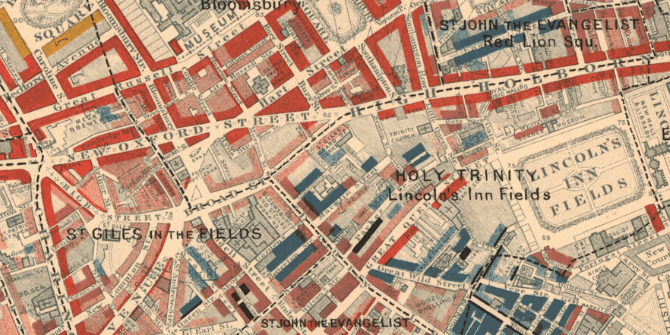

It was not uncommon for guiding literature, like Bradbury’s article to be used as an influence for the mapping of crime in cities. This map (right) is colour coded to represent the levels of poverty in London by working through streets where criminal classes all the way through to the upper classes lived.[14] Much like Charles Booths’ maps of Victorian London, Bradbury’s article acts as a linguistic version of this. He describes how the Walker Lane area is ‘the rammel grounds of crime and pestilence’ and ends his article by taking his readers to the more agreeable area and fresher air of Friar Gate and Ashbourne Road.

In an era of an increased effort to control working class morality by the middle and upper classes, Bradbury’s article offers valuable information. The language choices used by Bradbury shows a sense of othering against those that found themselves unfortunate enough to be at the bottom end of the social hierarchy. Whilst there is definitely a sense of dramatic licence in Bradbury’s work, the narrative put on display is no different to what is seen in other slum literatures.

This article by Bradbury in The Derby Mercury is useful for historians to better understand disorder within Derby slums, whilst also building on the slum narrative within England.

[1] Bradbury, E., Pictures of the Peaks (London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Co., 1891).

[2] Koven, S., Slumming: Sexual Social Politics in Victorian London (Princeton: Princeton University Press). Pp. 16

[3] National Archives, ‘Currency Converter’. Available Online: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result. Date Accessed: 12th January 2023.

[4] Ingleby, M., ‘Charles Dicken and the push for literacy in Victorian Britain’ (10th June 2020). Available Online: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/media/news/2020/hss/charles-dickens-and-the-push-for-literacy-in-victorian-britain.html#. Date Accessed: 12th January 2023.

[5] Flanders, J., ‘Prostitution’, Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians (15th May 2014). Available Online: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/prostitution. Date Accessed: 12th January 2023.

[6]Edward Bradbury, ‘Half-Days in Derbyshire: Half-Days in Derby (continued)’, The Derby Mercury, 1st November 1899. Pp. 7

[7] Walkowitz, J. R., and Stimpson, C. R., City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (London: Virago Press, 1992). Pp. 4

[8] Frenzel, F., Koens, K., and Steinbrink, M., (eds) Slum Tourism (London: Taylor and Francis, 2012). Pp. 2

[9] Frenzel, F., Koens, K., and Steinbrink, M., (eds) Slum Tourism. Pp. 2

[10] Madame Tussauds London, ‘Chamber of Horrors’. Available online: https://www.madametussauds.com/london/whats-inside/experiences/chamber-of-horrors/chamber-of-horrors-information-page/. Date Accessed: 12th January 2023.

[11] Bailey, Shore, and Philips, quoted in Alker, Z., ‘Street Violence in Mid-Victorian Liverpool’, Doctor of Philosophy, Liverpool John Moores University, February 2014. Pp. 73

[12] Royal Commission on Penal Servitude (1863), quoted in Alker, Z., ‘Street Violence in Mid-Victorian Liverpool’, Doctor of Philosophy, Liverpool John Moores University, February 2014. Pp. 72

[13] Alker, Z., ‘Street Violence in Mid-Victorian Liverpool’, Doctor of Philosophy, Liverpool John Moores University, February 2014. Pp. 72

[14] London School of Economics, BOOTH/E/1/6, Map Descriptive of London Poverty 1898-1899. Sheet 6. West Central District

Covering: Westminster, Soho, Holborn, Covent Garden, Bloomsbury, St Pancras, Clerkenwell, Finsbury, Hoxton and Haggerston, 1889-1897