By Mark Gratton

The 17th August 1836 saw a new government department formed; this was The General Register Office. It was tasked with generating and disseminating information from England and Britain. This might not have been the birth of statistics, but it was from this period on, that saw the growth of bureaucracy within England and Britain.[1]This growing use of data led to conflict between local and national government through the use of these new bureaucratic frameworks. This legislative struggle had a detrimental effect on the poor in society, this can be seen in Walker Lane, Derby.

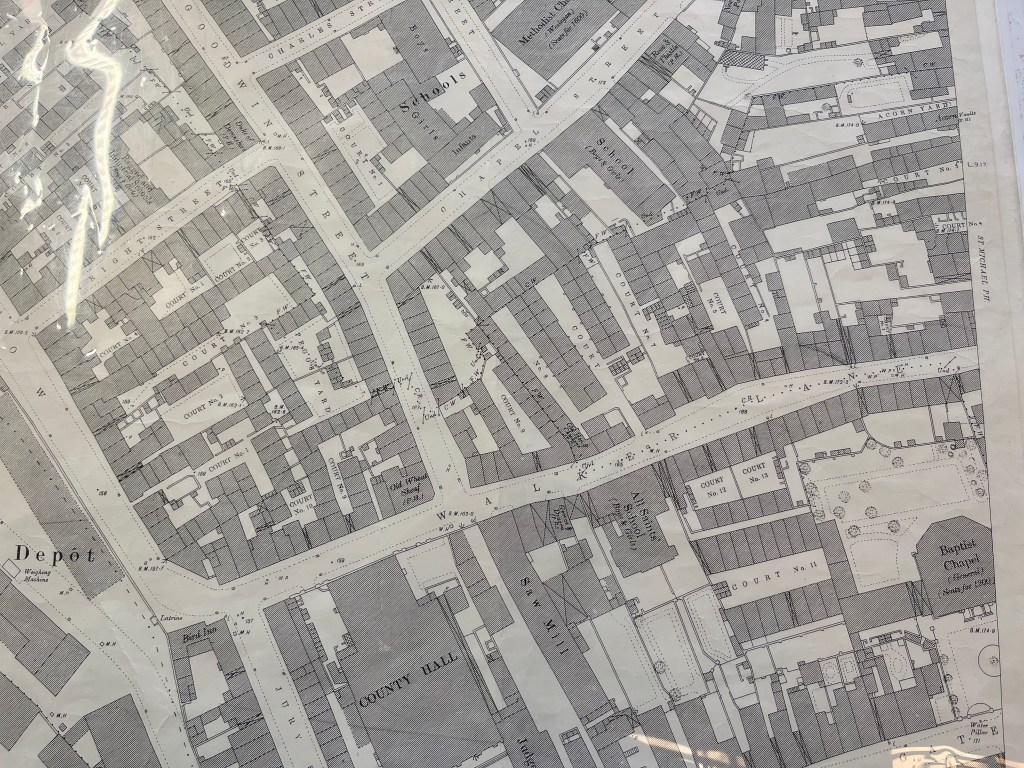

Walker Lane was part of the West End slum of 19th century Derby and as part of this slum it became synonymous with social problems including, disease, immorality, and crime. There might be some truth in these images; however, the bureaucratic wranglings around the sewage, drainage, and supply of water to Walker Lane, heightened and prolonged the societal problems.

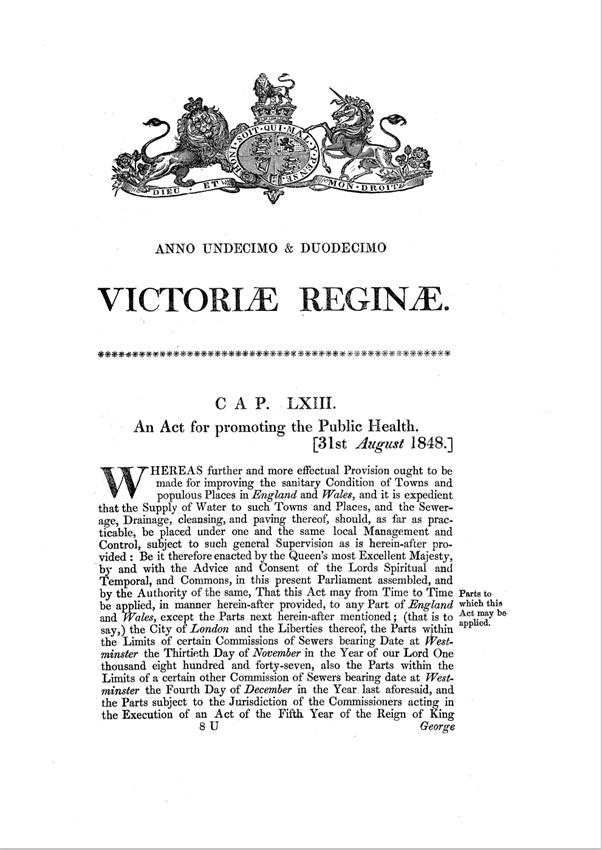

In 1849 Edward Cresy was appointed by the Board of Health to compile a report on the sewage, drainage, supply of water, and also the sanitary conditions of the residents of the Borough of Derby.[2] This report was conducted as part of the implantation of the Public Health Act 1848.[3] This Act was brought in to help centralise and standardise sewage, drainage and water supply to the towns and cities of Britain.

Cresy wrote extensively about Walker Lane and he provided an overview of how the Lane was structured and where it was situated within Derby. Also, within this overview he seemed to pass a moral judgement on some of the residents of Walker Lane. He wrote,

‘ The houses are of the most inferior description, and the inhabitants of a piece with their houses; to crown all, there are lodging houses, which are the principal headquarters of vagrants, and of these comers and goers who for reasons best known to themselves prefer darkness to light.’[4]

Edward Cresy

Debolina Dey describes this form of judgement as ‘Pathologising Poverty.’[5] Furthermore, she highlights the combination of the New Poor Law 1834, Edwin Chadwick’s Sanitary Report 1842, and the Public Health Act 1848 for providing the framework for categorising the poor.[6]

This moralistic judgement runs throughout Cresy’s report, and his scorn is not reserved only for the poor. He highlights the lack of progress regarding drainage and water supply to the poorer roads and courts within Derby, whilst noting that work has taken place in other areas of town.[7] Cresy concludes his report by reiterating the failures of the local authorities and he goes on to write, ‘Few towns have more need of the provision of the Public Health Act being applied to them than Derby.’[8]

This report created a bureaucratic backlash from the local authorities within Derby. The Commissioners appointed a committee to consider the Cresy report and then present their findings to the general meeting of Commissioners.[9] The condemnation of the Cresy report is scathing and inflammatory in nature. They write about Cresy,

‘Before entering upon the subject, they cannot but express their regret that any Public Officer should have ventured to make a report so full of mis-statements and exaggerated assertions, and altogether so loose and inaccurate in its details, that any inferences drawn from it cannot do otherwise than mislead the judgement of the Board of Health, for whose guidance it is intended.’[10]

Commissioners Report

This counter report goes on to use other bureaucratic legislation to defend its position. It alludes to the better use of both the Nuisance and Improvement Acts to control the problems, it seems to suggest that the use of these acts would solve the problems on Walker Lane.[11] This approach again delivers a moralistic judgement on the residents of Walker Lane, suggesting that better behaviour would improve the sanitary conditions.

The Public Health Act was a piece of legislation that was designed to improve the health of the nation; however, one can see that through this case study of Walker Lane that was not always the outcome. Whilst improvements to the wealthiest areas of Derby had taken place, it was the working-class areas that needed the help of this legislation and report. Steven Novak states that one needs understand the motivations of the people writing the reports to understand some of their conclusions, there is often a case of self-promotion within them.[12] The bureaucratic battle surrounding the Cresy report proved detrimental to the poorest within Derby society, as the drawn-out process of improvements to drainage, sewage and water supply affected them the greatest.

[1] Wolfenstein, GabrielK. “Recounting the Nation: The General Register Office and Victorian Bureaucracies.” Centaurus, vol. 49, no. 4, 2007, pp. 261–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0498.2007.00083.x. p.261

[2] Cresy, Edward. Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage and supply of water, and the sanitary conditions of the inhabitants of the Borough of Derby. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library. https://emlib.ent.sirsidynix.net.uk/client/en_GB/search/asset/162/0

[3] Public Health Act 1848. Public Health Act 1848 (legislation.gov.uk)

[4] Cresy, Edward. Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage and supply of water, and the sanitary conditions of the inhabitants of the Borough of Derby. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library. https://emlib.ent.sirsidynix.net.uk/client/en_GB/search/asset/162/0 p.13

[5] Dey, Debolina. “Pathologizing Poverty.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 2021.

[6] Dey, Debolina. “Pathologizing Poverty.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas, 2021.p.5.1

[7] Commissioners Under the Derby Improvement Act. Committee Appointed by Them Conjointly with the Lamp and Road Committee, to Consider Mr Edward Cresy’s Report to the General Board of Health. 1849. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library.

[8] Cresy, Edward. Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage and supply of water, and the sanitary conditions of the inhabitants of the Borough of Derby. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library. https://emlib.ent.sirsidynix.net.uk/client/en_GB/search/asset/162/0 p.38/51

[9] Cresy, Edward. Report to the General Board of Health on a preliminary inquiry into the sewerage, drainage and supply of water, and the sanitary conditions of the inhabitants of the Borough of Derby. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library. https://emlib.ent.sirsidynix.net.uk/client/en_GB/search/asset/162/0 p.51

[10] Commissioners Under the Derby Improvement Act. Committee Appointed by Them Conjointly with the Lamp and Road Committee, to Consider Mr Edward Cresy’s Report to the General Board of Health. 1849. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library. p.3

[11] Commissioners Under the Derby Improvement Act. Committee Appointed by Them Conjointly with the Lamp and Road Committee, to Consider Mr Edward Cresy’s Report to the General Board of Health. 1849. Derby Local Studies and Family History Library. p.8

[12] NOVAK, SJ. “PROFESSIONALISM AND BUREAUCRACY – ENGLISH DOCTORS AND VICTORIAN PUBLIC HEALTH ADMINISTRATION.” Journal of Social History, vol. 6, no. 4, 1973, pp. 440–62, https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/6.4.440. p.443